Single cavitating lesion

On chest X-Ray and CT

Introduction

A single cavitating lung lesion can signal something benign or malignant. In this article we’ll go through two cases, firstly the case of a woman in her 50s with right-sided chest pain, with a finding you may not spot initially that changes the diagnosis.

We will go through how to approach single cavitating lesions, the differential diagnosis, how to spot subtle but critical signs of malignancy, and why checking the bones in detail is important.

Case one introduction

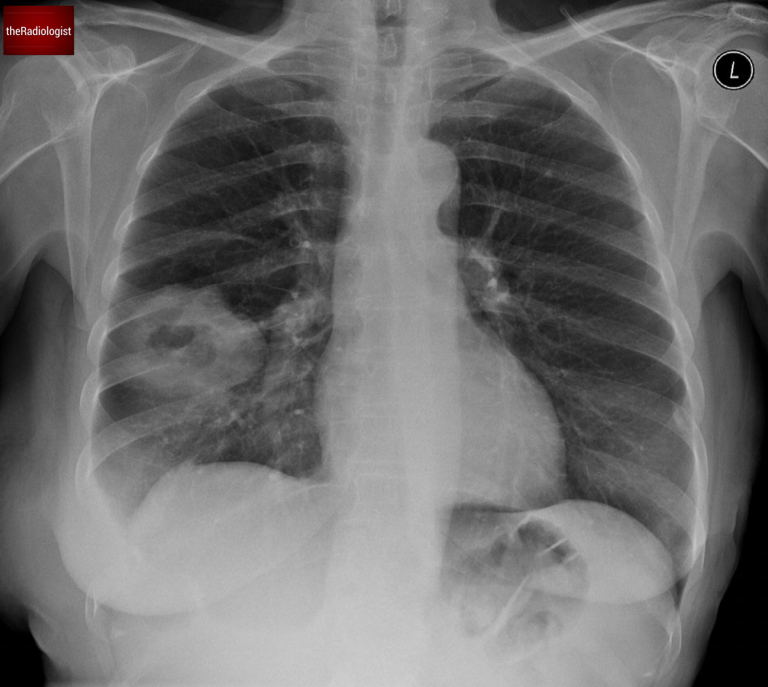

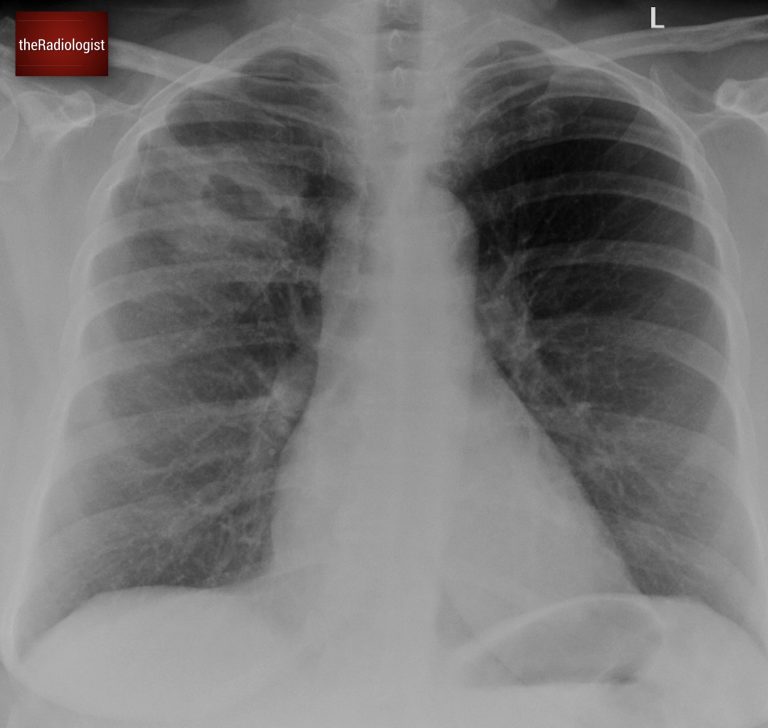

A woman in her 50s went to her GP with right-sided chest pain. Have a look at the initial chest X-Ray below:

PA Chest X-Ray

Video explanation

Here is a video explanation of this case: click full screen in the bottom right corner to make it big. If you prefer though I go through this in the text explanation below.

Differential for a single cavitating lesion

We can see a single cavitating lesion within the right lung. Cavitation refers to the presence of a region of gas within a solid lesion. The differential for multiple cavitating lesions is wide but in practice when I see a single cavitating lesion the differential narrows to two main categories:

1. Infection

- Bacterial causes like Staphylococcus aureus or Klebsiella

- Fungal infections

- Tuberculosis (TB)

2. Lung Cancer

Especially squamous cell carcinoma, though other types can occasionally cavitate.

Have another look at the cavitating lesion. In this case, the lesion’s thick walls were a red flag, pointing towards malignancy. But this on its own wasn’t enough to confirm the diagnosis. There is however another sign on the film that is more specific.

See how the lesion in this case has a thick wall.

Reviewing the bones

This is where things get interesting. Let’s review the bones.

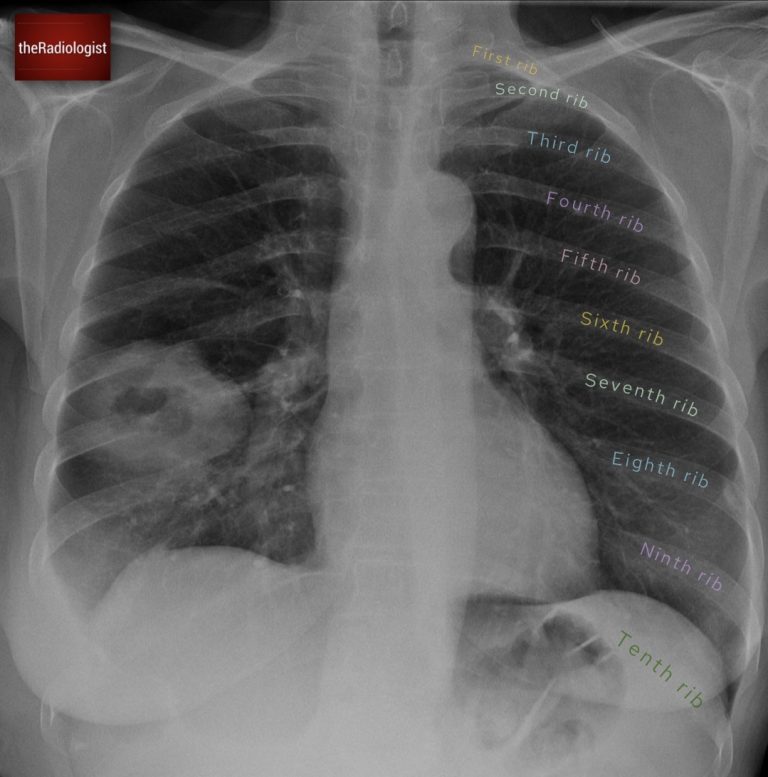

Examine the chest X-ray systematically and first have a look at all of the ribs on the left.

Firstly outline all of the ribs on the left: no issues here, we can see all of them.

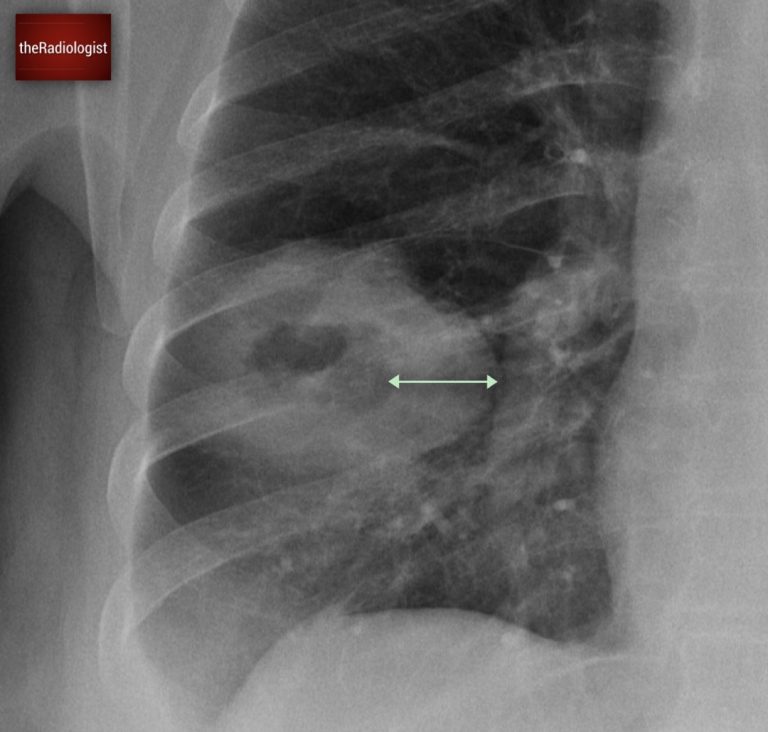

Now have a look on the right, outline all of these ribs and compare with the left. Any problems here?

If you look carefully, you will see the right ninth rib is missing. Now, this is significant. If there’s no history of surgery, the absence of a rib usually means it has been destroyed. And while infections like TB can sometimes cause partial erosion, complete rib destruction almost always points to lung cancer.

This time if you outline the right sided ribs and compare side by side you will find the ninth rib is missing.

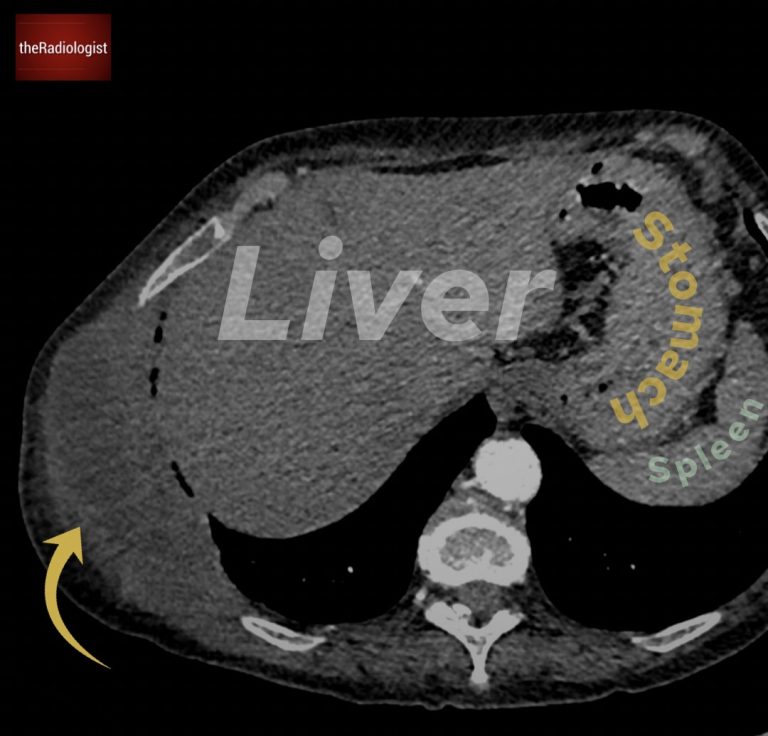

Workup

To solidify the diagnosis and to stage the patient, a CT scan was performed. As well as the cavitating lesion within the lung, it revealed a large mass invading the chest wall, clearly eroding the ninth rib. This finding strongly supported the suspicion of malignancy.

An ultrasound-guided biopsy of the chest wall mass was then carried out, confirming the presence of lung cancer with a large chest wall metastasis.

There is a soft tissue mass within the right chest wall destroying the ninth rib.

KEY POINT

Don’t miss a missing rib!

Rib destruction can be a subtle yet crucial finding that can shift the diagnosis from infection to malignancy.

A whole rib missing can sometimes be more difficult to appreciate than partial rib erosion: I usually make the film small and compare side by side just to make sure all the ribs are present.

Case two introduction

A single cavitating lesion does not always mean lung cancer. In a separate case, a female patient in her 60s presented with a history of cough and fever, along with imaging that showed a cavitating lesion in the right lung. Have a look at the X-Ray below:

PA Chest X-Ray

Case two findings and workup

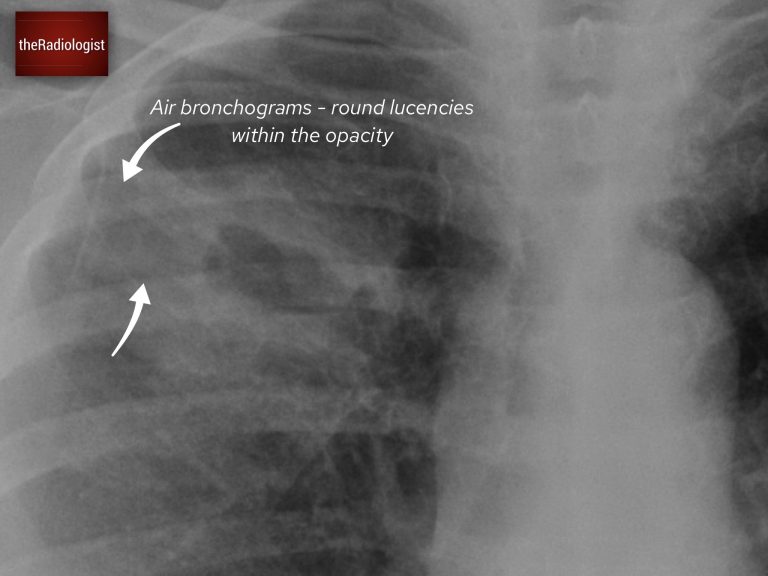

The X-ray revealed a cavitating lesion surrounded by consolidation. How do we know this is consolidation? Look for air bronchograms: small, round lucencies within the opacity, a hallmark of consolidation.

There are air bronchograms surrounding the cavitating lesion suggesting the presence of consolidation.

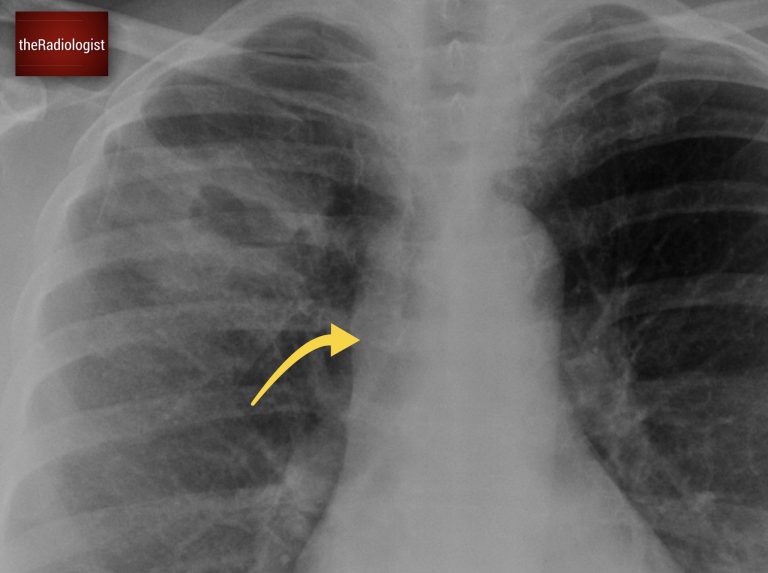

Unlike the previous case, there was no rib destruction. However, there was increased density within the right paratracheal region and an enlarged azygos contour.

This points towards right sided paratracheal lymph node enlargement. Bulky lymph nodes can point more towards cancer however mild node enlargement can be seen in both infections and cancer.

Look at the right paratracheal region: we have loss of the right paratracheal stripe and there is increased density in this region suggesting nodal enlargement.

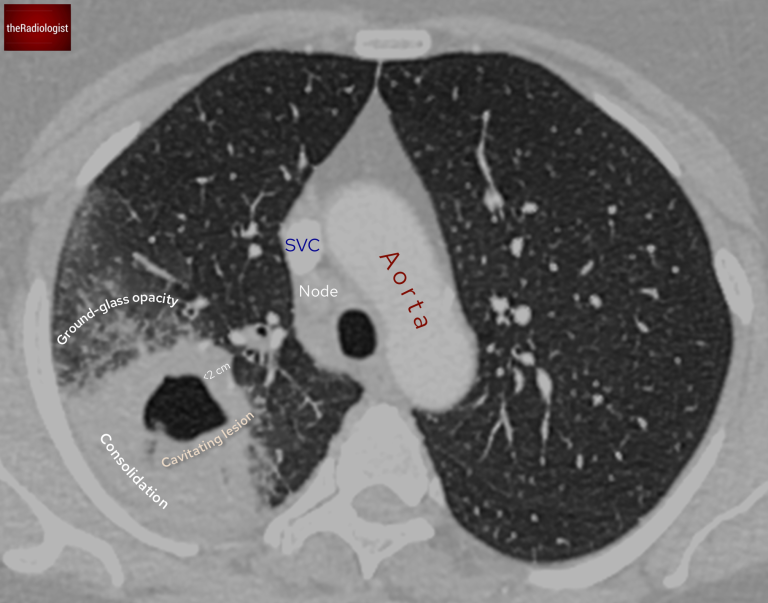

A CT scan provided further clarity:

- The lesion’s wall thickness was measured at less than 2 cm.

- Surrounding ground-glass opacity and consolidation were noted.

- The right paratracheal lymph node enlargement seen on X-ray was confirmed.

The wall of the cavitating lesion measures at less than 2 cm and there is surrounding consolidation and groundglass opacity.

Studies, such as one published by Nin et al. in Clinical Radiology (2016), offer some helpful pointers to distinguish between infection and malignancy in these cases:

- Wall thickness:

- Lesions with walls thicker than 2.4 cm were more likely to be malignant.

- Walls thinner than 7 mm were more likely to represent benign causes.

- Look for consolidation and centrilobular nodules:

- Features like consolidation or centrilobular nodules are more indicative of infection.

In this case, the wall thickness was less than 2.4 cm so we cannot say this is more likely cancer. The surrounding consolidation reinforced the likelihood of a benign cause.

To add to the evidence, the patient had raised inflammatory markers and symptoms of cough and fever. These pointed strongly toward an infective cause rather than malignancy.

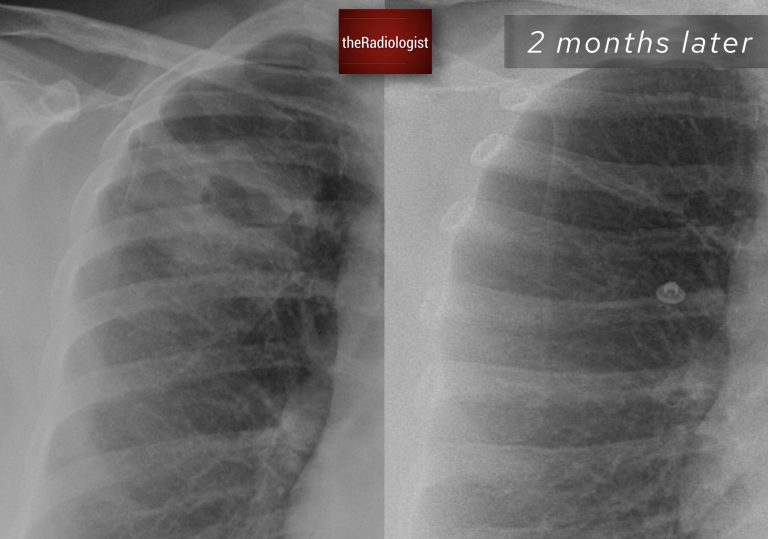

The patient was treated with antibiotics, and a follow-up X-ray showed complete resolution of the lesion, confirming an infective etiology.

Follow up chest X-Ray at 2 months shows resolution of the right sided cavitating lesion.

Learning points

1. Wall Thickness and Surrounding Features Offer Clues

- Thick walls (>2.4 cm): Think malignancy.

- Thin walls (<7 mm) with consolidation or nodules: Point to infection.

2. Leverage the Clinical Picture

- Infection: Look for fever, cough, elevated inflammatory markers, and resolution after treatment.

- Cancer: Look for systemic signs like weight loss and rib destruction.

3. Imaging Follow-Up and Biopsy

If the lesion is suspicious for malignancy, it is wise to proceed with PET-CT with a view to CT guided biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. If infection is more likely, follow-up imaging can often provide reassurance. Sputum/blood culture and even bronchoscopy can help prove the presence of a causative organism.

If there is persistence of the lesion on follow up imaging with no improvement in the cavitating lesion at that point PET-CT and biopsy can be considered.