Abdominal X-Ray review areas

A system for reviewing abdominal X-Rays

Introduction

CT dominates modern abdominal imaging and in a lot of centres has replaced the abdominal film as the initial imaging investigation of choice in acute abdominal pain.

The abdominal X-Ray however does have a role to play in some parts of the world and remains quick, accessible, and often revealing.

Interpretation depends on pattern recognition and consistency. In this article we will work through a system to help you interpret what can be a tricky film to assess.

Background

Abdominal X-rays are ordered far less frequently now than they used to be.

The main reason is although the radiation dose is lower than an abdominal CT (although considerably higher than a chest X ray) the diagnostic yield of an abdominal film is limited compared with CT. For example although an abdominal X-ray can diagnose bowel obstruction a negative film does not exclude these conditions. Also most of the time when you find bowel obstruction a CT scan will be performed anyway to establish the cause. Abdominal X-ray also has less sensitivity than CT for other acute pathology such as ischemic bowel, perforation and abdominal collections.

So abdominal X-rays have been phased out in the acute setting although in some parts of the world where CT is less readily available it still provides part of the acute workup. The advantages are that it is fast and accessible. It still provides some benefits in the outpatient setting in cases of faecal loading and assessing colonic transit as well as in the acute setting in monitoring inflammatory bowel disease and known diagnoses of small bowel obstruction.

For that reason, it’s important to know how to interpret one properly.

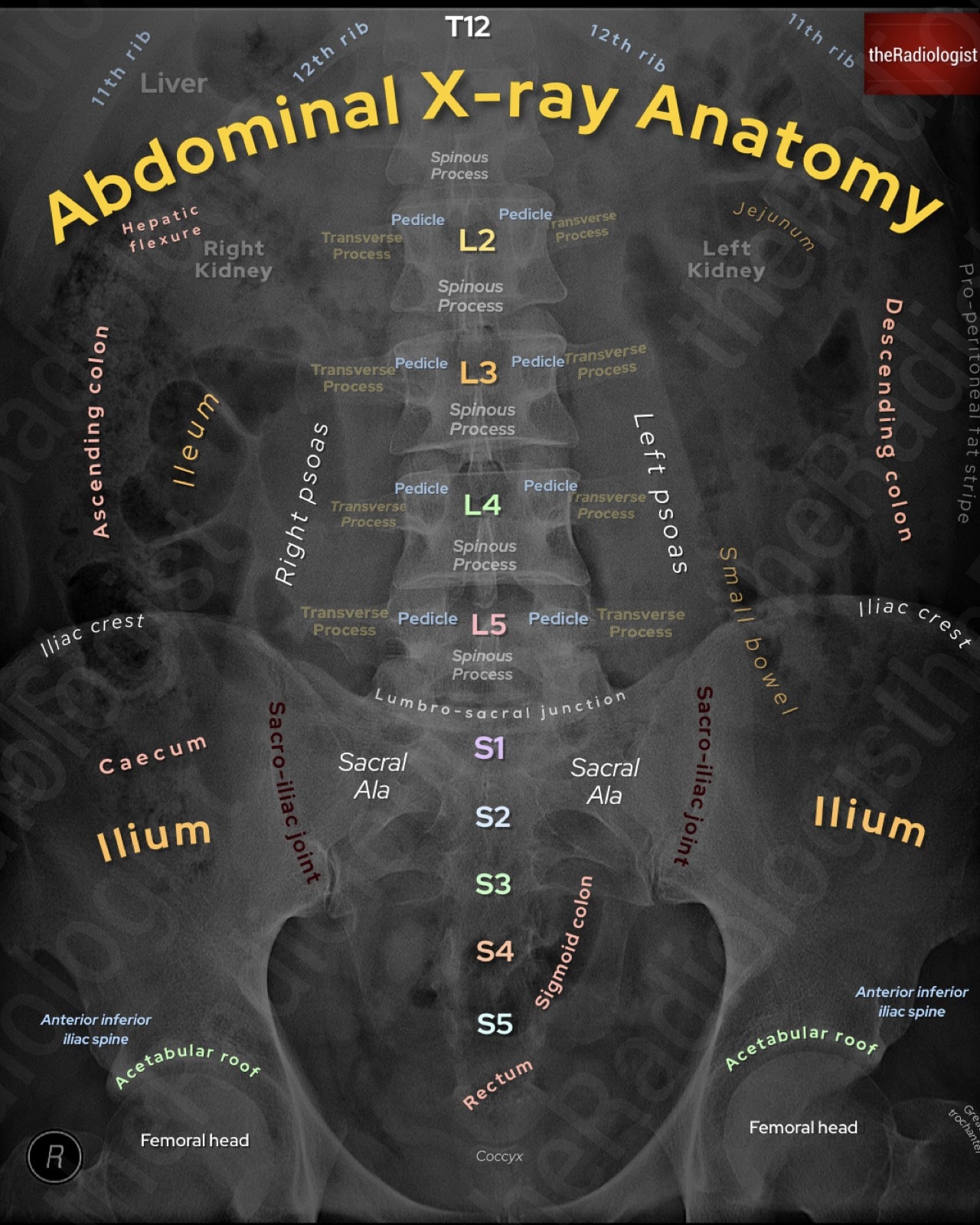

Annotated view of an abdominal X-Ray

As a student, I found abdominal X-Rays particularly challenging because the appearances can be subtle and the films often look cluttered compared with chest X-rays. What helped me was adopting a systematic approach. The system I now teach and use myself is the mnemonic AC POP: standing for Air, Calcification, Psoas, Organomegaly/Soft tissue, and Pelvis/Spine.

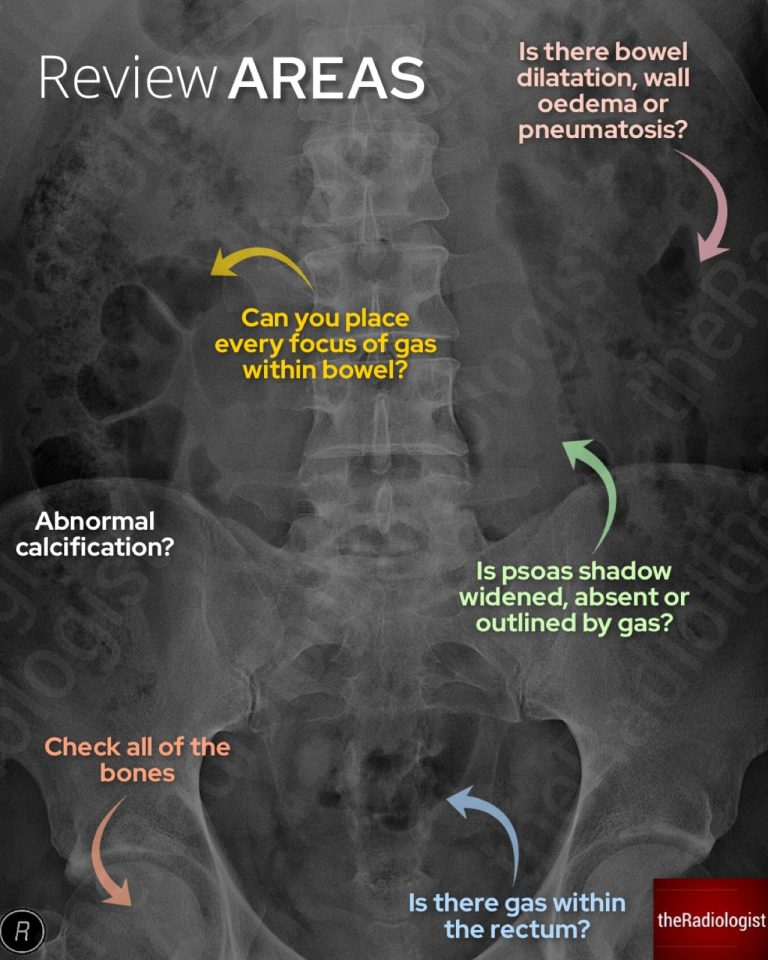

Abdominal X-Ray review areas

A: Air

The first step is to track every lucency you see on the film. Ask yourself: does each pocket of gas sit within bowel, or is any of it free? Triangular collections of gas are especially suspicious for extraluminal air and often reflect perforation. Look also for the football sign: a large oval lucency outlining the peritoneal cavity, often seen in children.

Also check carefully for Rigler’s sign: the ability to see both sides of the bowel wall due to free intraperitoneal gas. This can be striking in obvious cases but subtle in early perforations.

Now assess bowel calibre. Small bowel is considered dilated if it exceeds 3 cm, large bowel 5 cm, and caecum up to 9 cm. When bowel is dilated, decide whether this could represent complete mechanical obstruction. Absence of rectal gas supports this, although the presence of rectal gas does not exclude a significant obstruction.

Where you see the bowel helps differentiate between small and large bowel. Dilated small bowel tends to be central, with valvulae conniventes traversing the full width of the bowel. Dilated large bowel lies more peripherally and shows haustra that do not cross the entire wall.

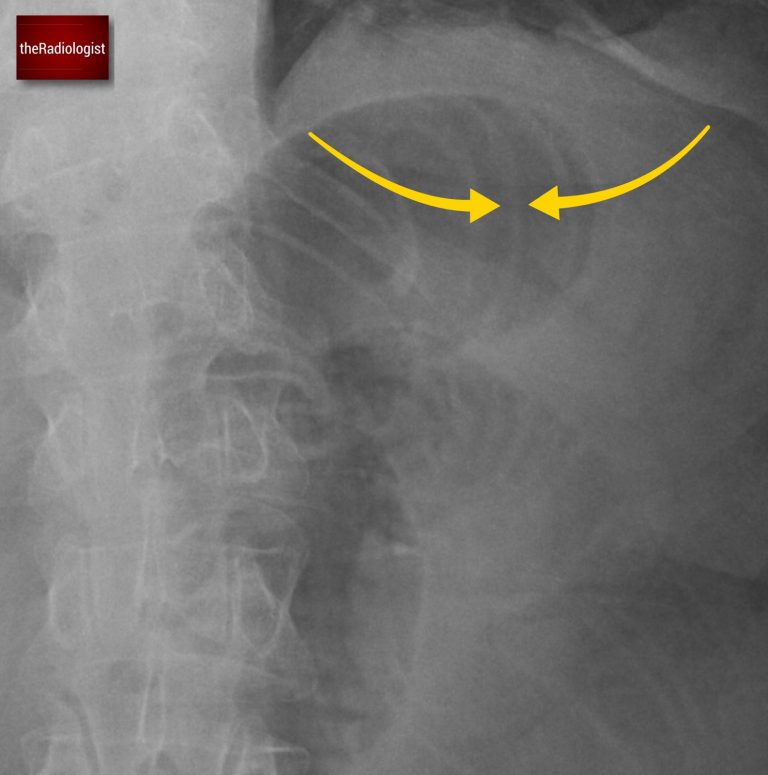

A case of large bowel obstruction. Here is the transverse colon and we can see indentations called haustrae that do not traverse the whole bowel wall.

A case of small bowel obstruction. Here we can see indentations called valvulae conniventes which unlike haustrae do traverse the whole bowel wall.

Let’s look at a table comparing the differences on X-Ray between large and small bowel obstruction:

| Small | Large | |

|---|---|---|

| Diameter of bowel loops when obstructed | >3 cm | >5 cm (>9 cm if caecum) |

| Indentations seen | Valvulae conniventes (traverse whole bowel wall) | Haustrae (just periphery) |

| Location | Central | Peripheral |

KEY POINT

Valvulae conniventes traverse the whole bowel and are seen in small bowel loops.

Haustrae do not traverse the whole bowel wall and are seen with large bowel.

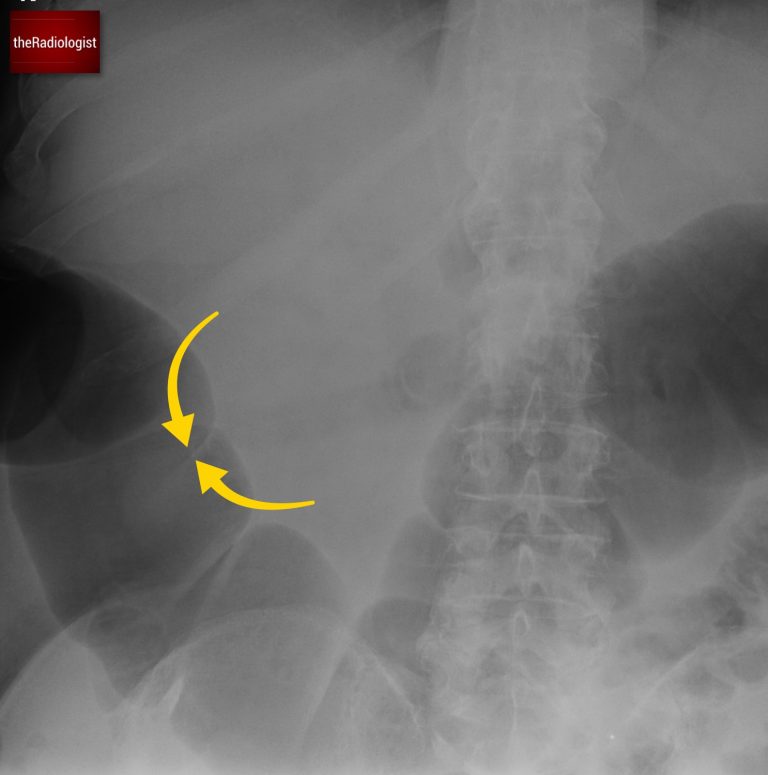

If you see a single massively dilated loop of bowel on AXR, always consider volvulus. The two most common sites are the sigmoid and the caecum.

Sigmoid volvulus, more common in older patients, often shows the coffee bean sign: a large, smooth loop without haustra. Caecal volvulus tends to occur in younger patients and usually preserves the haustral pattern. Gas visible in the caecum and ascending colon favours sigmoid rather than caecal volvulus.

Have a look at this case which helps look at some of the key features of volvulus.

Don’t forget to check for pneumatosis intestinalis: mottled lucency within the bowel wall, usually a marker of ischaemic bowel although it can be seen in more chronic causes such as COPD, steroid therapy and connective tissue disease. If suspected, look at the liver for branching peripheral lucency representing portal venous gas: if you see this you know you are dealing with ischemic bowel and unfortunately if seen in adults this carries a poor prognosis.

Remember gas within the liver is not always due to portovenous gas. This will usually be peripheral whereas gas within the billary tree ie aerobilia, will be more central. Aerobilia is most commonly seen in iatrogenic cases of biliary intervention but also can be found in gallstone ileus where a gallstone erodes through the gallbladder and into the small bowel causing obstruction. So if you see both small bowel dilatation and gas within the liver on abdominal film have a think about gallstone ileus.

Also assess the bowel for ‘thumbprinting’ which can suggest mural thickening and indicate a colitis. The aetiology of this varies and includes inflammatory bowel disease, ischaemic colitis, infective and radiation colitis.

Indentations within the bowel wall represents ‘thumbprinting’ and reflects mural thickening seen with colitis.

C: Calcification

Abnormal calcifications are often best appreciated on AXR. Work through the following:

- Pancreatic calcification may point to chronic pancreatitis.

- Appendicolith in the right iliac fossa is a potential marker of appendicitis.

- Gallstones or renal stones can occasionally be seen depending on their composition.

- Calcified aortic outline can reveal an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

P: Psoas

Outline the psoas shadows. They should taper cleanly towards the pelvis on both sides. Loss of definition may be due to overlying bowel gas, but true obscuration can suggest retroperitoneal pathology. The muscles may appear widened in cases of haematoma or abscess.

Gas tracking along the psoas margin is a red flag for retroperitoneal perforation, such as from the ascending or descending colon.

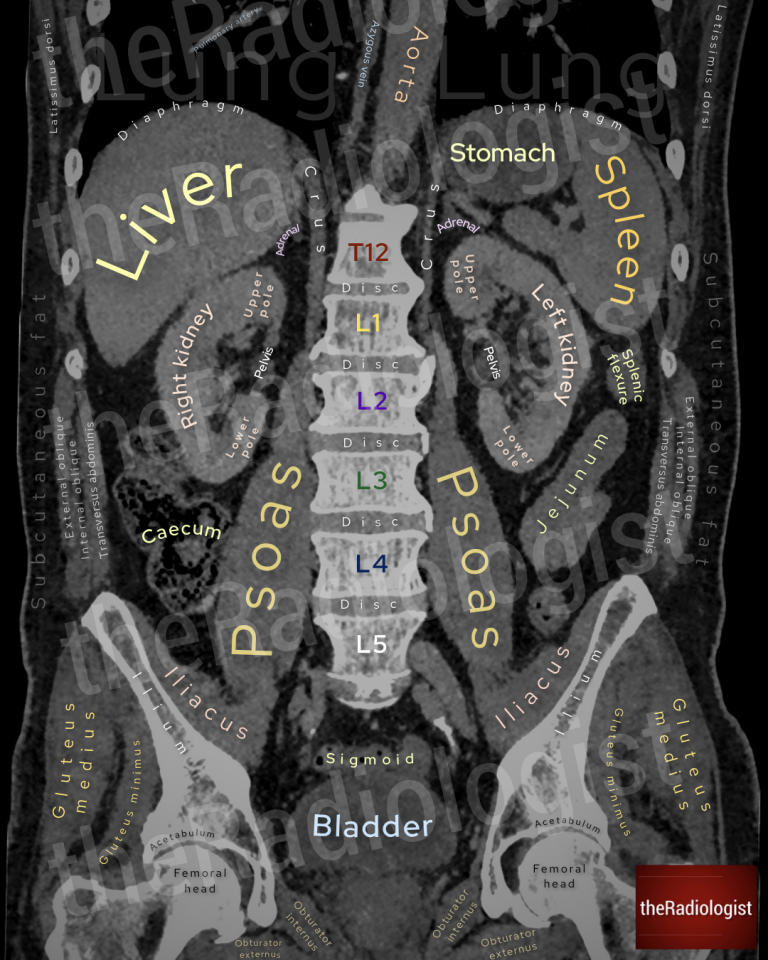

Note the position of the psoas muscles on this image of a coronal CT. On an abdominal film review the psoas muscles for loss of outline, expansion or adjacent gas.

O: Organomegaly and soft tissues

Although soft tissues are harder to evaluate than gas or bone on an X-Ray, you should still try to outline the main solid organs. Look for an enlarged liver extending below the costal margin, a spleen crossing the midline, or large kidneys as in polycystic kidney disease. Mass effect may also be inferred by effaced bowel loops displaced from their usual position.

If the bowel loops look more central than usual this could be due to ascites.

P: Pelvis and spine

Finally, don’t forget the bones. Check the pelvic ring carefully for fractures, particularly in the trauma setting.

The lumbar spine is visible in most abdominal films: assess vertebral height and alignment, looking for compression fractures or destructive lesions.

Final recap

Let’s recap the AC POP review system for abdominal X-Rays in this table:

| Mnemonic | Review area | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| A | Air | Track every lucency you can see. Triangles are suspicious for perforation. Look for dilated bowel, free gas, pneumatosis and portovenous gas/aerobilia. |

| C | Calcification | Look for abnormal calcification including within the pancreas, appendix, gallbladder, kidneys and aorta. |

| P | Psoas | Assess for expansion, loss of outline or adjacent gas representing a retroperitoneal perforation involving ascending/descending colon, duodenum or upper rectum. |

| O | Organomegaly and soft tissues | Try and outline any organs you can see – you may spot an enlarged liver or polycystic kidneys. Central bowel loops can reflect ascites. |

| P | Pelvis and spine | Check the bones for bone lesions and fractures in particular. |