Assessing a white-out

On a frontal chest X-Ray

Introduction

Finding a white-out on Chest X-Ray can be an alarming finding.

Knowing how to deduce the cause can be tricky but there are skills we can use to accurately make the diagnosis just from the initial frontal Chest X-Ray.

In this article we will go through the workup of a male in his 70s who presented with a white-out and then have a look at the management of large pleural effusions in particular.

Case introduction

A male in his 70s presents to the Emergency Department which breathlessness.

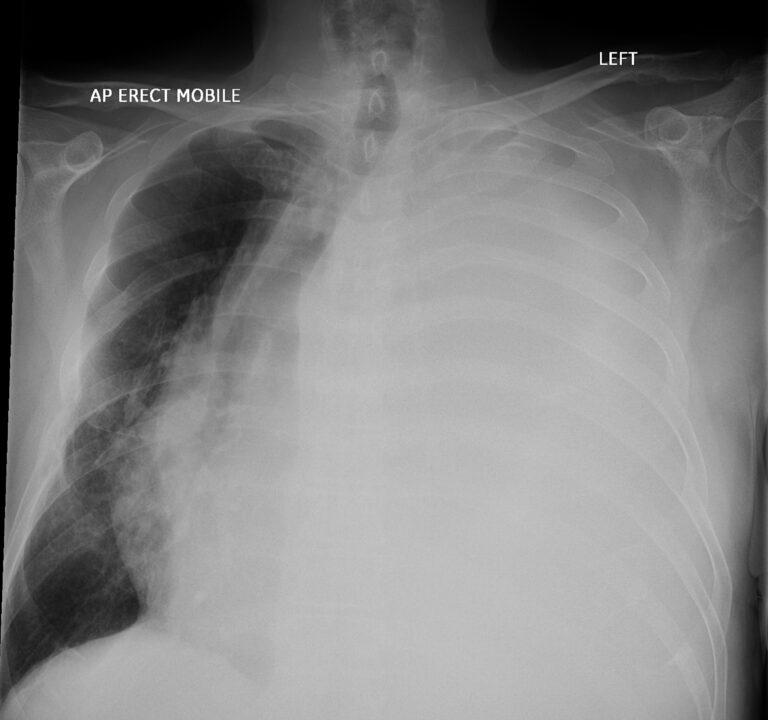

Have a look at the Chest X-ray below:

AP view of a Chest X-Ray of a male in his 70s presenting with breathlessness

Video explanation

Here is a video explanation of this case: click full screen in the bottom right corner to make it big. If you prefer though I go through this in the text explanation below.

How to assess a white-out

The X-ray is clearly not normal. The left side is completely opacified: this can be termed a white-out. By looking at the mediastinum we can try and work out the cause.

| Mediastinum position | Cause of white-out |

|---|---|

| Pushed away from white-out | Pleural effusion |

| Pulled towards white-out | Lung collapse or pneumonectomy |

| Position unchanged | Consolidation |

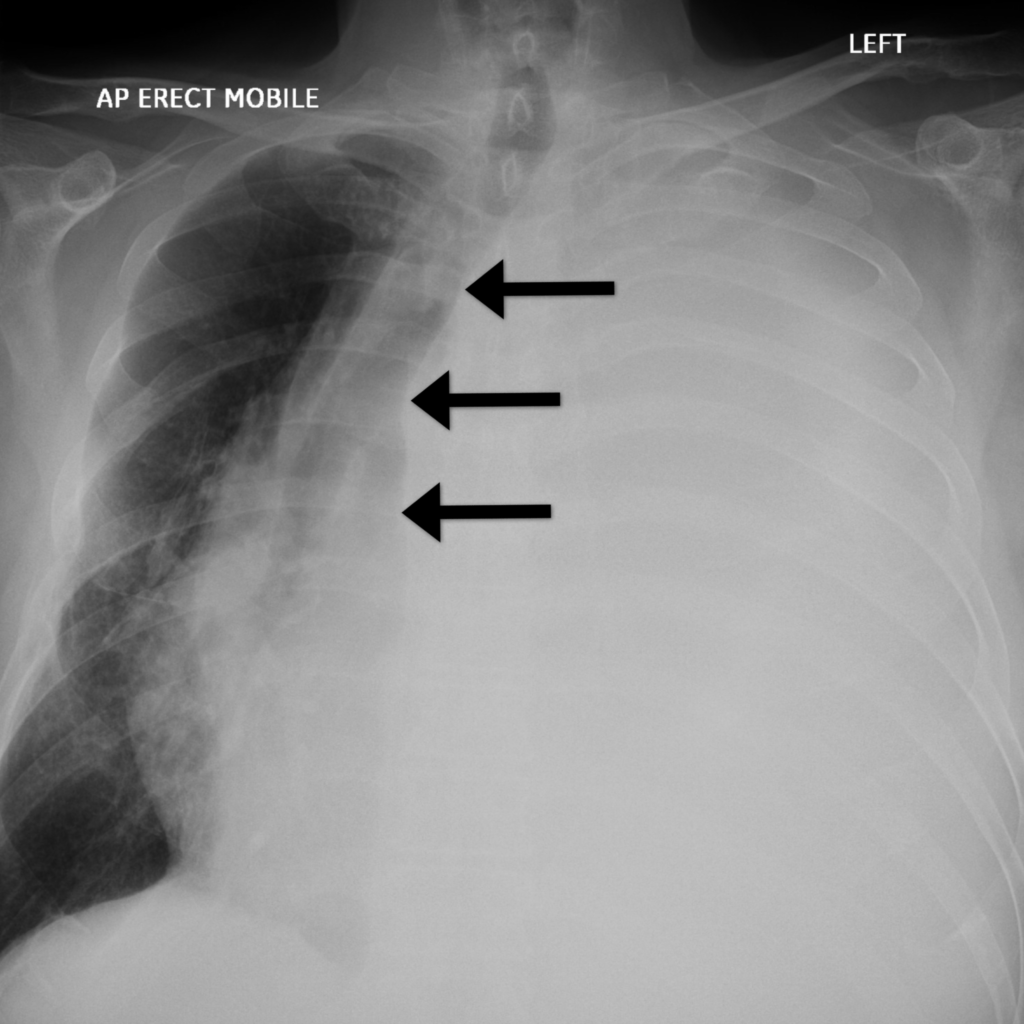

In this case we can see the mediastinum is pushed away from the white-out: look at the position of the trachea in the X-ray below.

Given there is movement away from the white-out we have to strongly suspect a pleural effusion. The fluid within the pleural space occupies volume which exerts pressure upon the mediastinum.

The next step here depends on the availability of services in your local hospital but an ultrasound can help to firstly confirm the presence of pleural fluid and secondly help guide aspiration and drainage of the effusion. Taking fluid off has two purposes: firstly it can be diagnostic in terms of testing for cytology, biochemistry and microbiology but it is also therapeutic for the patient, especially when you have such a big effusion causing mass effect on the mediastinum.

In terms of biochemistry we can look at the level of protein level to help us decide on the cause of the pleural effusion. Exudates have a protein level of >35 g/dL, transudates have a protein level of <25 g/dL whilst between 25-35 g/dL we can use Light’s criteria to decide if an exudate or transudate.

If the pleural total protein divided by serum total protein is more than 0.5 we can consider the fluid to be an exudate. Alternatively if the pleural LDH level divide by serum LDH level is over 0.6 again we can say this is an exudate.

Let’s look at some of the important causes of exudates and transudates below:

| Exudate (>35 g/dL) | Transudate (<25 g/dL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection | Including a parapneumonic effusion as well as empyema: here you expect purulent fluid and a pH of <7.2 | Congestive heart failure | Bilateral effusions common. Look for other signs of heart failure on X-Ray and clinically as well as a raised BNP level. |

| Malignancy | Either primary (mesothelioma) or secondary metastatic disease from a distant primary | Liver cirrhosis | Right sided effusion more common |

| Inflammatory | Causes include rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, acute pancreatitis | Hypoalbuminemia | Often bilateral and small with abdominal fluid in addition |

| Pulmonary embolism | Small pulmonary emboli can be associated with transudates. Pleural inflamation and infarction can be associated with an exudate. | Nephrotic syndrome | May also see peripheral oedema and ascites. Usually bilateral. |

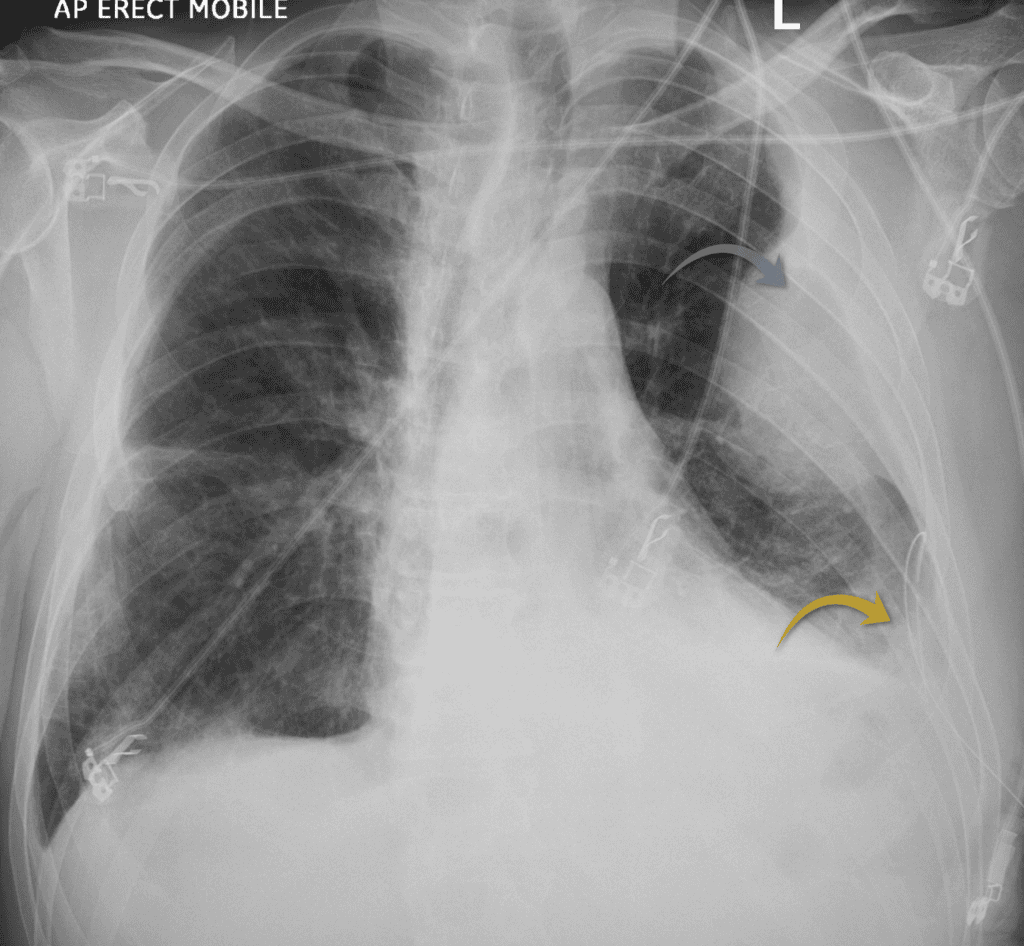

In this case draining the pleural effusion revealed some interesting findings. Have a look at the post drainage X-ray below.

In this case the trachea is deviated to the right, pushed away from the white-out suggesting a pleural effusion

Post-drainage

We can see the chest drain is now in place (yellow arrow) and there has been a marked improvement in the white-out and degree of mediastinal shift. There is however now an underlying mass (grey arrow).

This forms obtuse angles with the chest wall suggesting it may be pleurally based. An underlying pleural mass and an associated malignant pleural effusion needs to be suspected at this stage.

CT imaging would now be appropriate. What contrast phase would be best to assess this further? Venous phase CT is best when it comes to assessing pleural disease (rather than an arterial phase).

Left sided chest drain inserted into the left pleural effusion (yellow arrow) revealing an underlying mass (grey arrow)

CT scan assessment

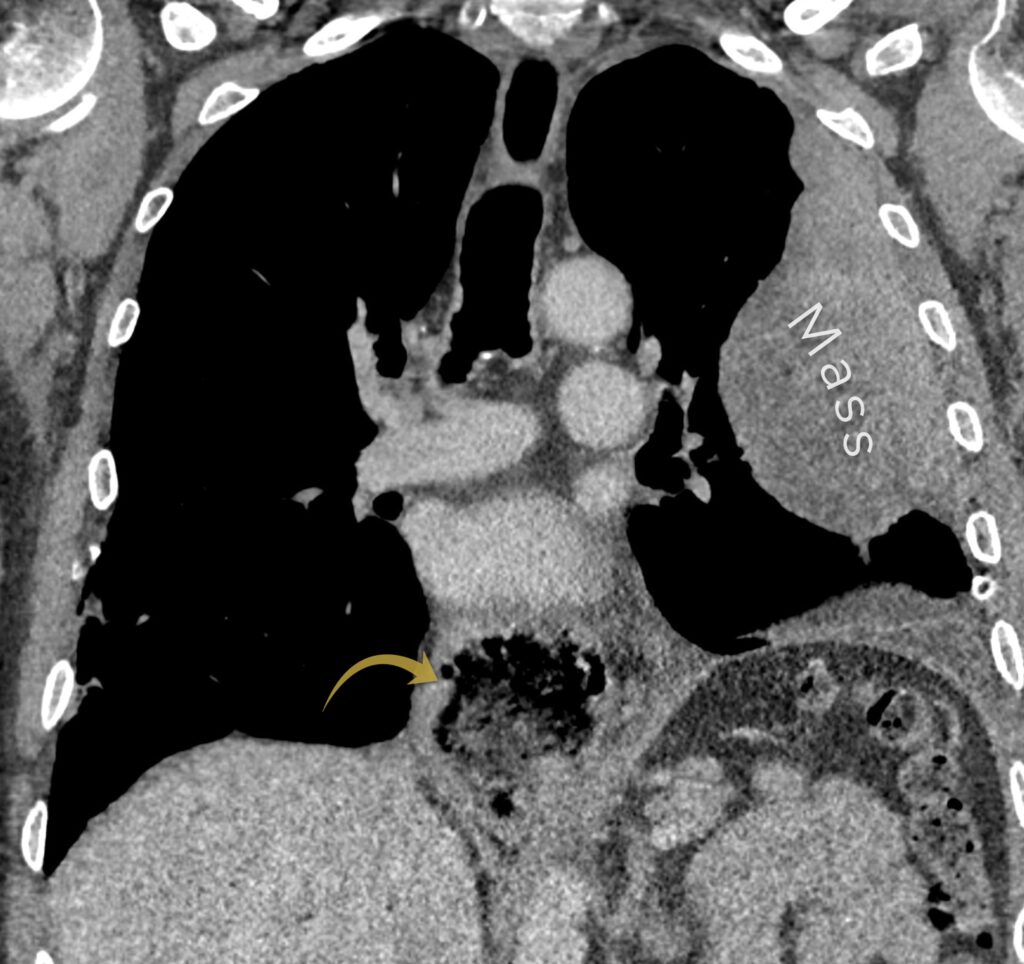

The CT confirms an enhancing mass related to the pleura. Again, the obtuse angle the mass forms with the chest wall tells us the lesion is related to the pleura rather than being a parenchymal lung mass.

Pleural mass confirmed on CT. Also have a look at the gastric pull up (yellow arrow)

CT also shows us something else: the oesophagus has been resected due to oesophageal cancer and the stomach has been pulled up (a ‘gastric pull up’). Having a diagnosis of cancer changes the picture, instead of a primary malignancy of the pleura, ie mesothelioma, we now have to consider metastatic disease of the pleura.

This is an easier diagnosis to make if there are metastases elsewhere but here there is no history of metastatic disease.

Have a look at the CT scan in more detail below:

The only way to be certain of the diagnosis is to obtain a sample for cytology or histology. The first step would be to send off the pleural fluid that was initially drained. Here that was negative and so the next step was to try and take a sample of the pleural mass. The best way to do that here is under US or CT guidance, in this case the biopsy was done under CT.

CT guided biopsy

In the image below we can see the biopsy needle is placed into the left pleural mass. We can again see the gastric pull up behind the trachea.

The sample confirmed a metastasis from the previous oesophageal cancer. Pleural disease is not a very common manifestation of oesophageal cancer and this case shows the importance of obtaining a tissue diagnosis.

CT guided biopsy of the left sided pleural mass confirmed a diagnosis of metastatic oesophageal cancer

KEY POINT

When you see a white-out, assess the mediastinum.

This then helps you decide between consolidation, collapse or a pleural effusion as the underlying diagnosis. Ultrasound can be a useful tool to help decide if the fluid can be drained safely.