Septic emboli

On chest X-Ray and CT

Introduction

Septic emboli can be easy to miss but dangerous to overlook. Recognising the imaging features and knowing when to suspect them is key, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms and there are some classic imaging findings.

In this case, we walk through the chest X-ray and CT findings, explore the differential for multiple lung nodules, and highlight the steps to track down the source. A useful case to help you spot the clues, think through the differential, and see how imaging can steer the whole diagnosis.

Case introduction

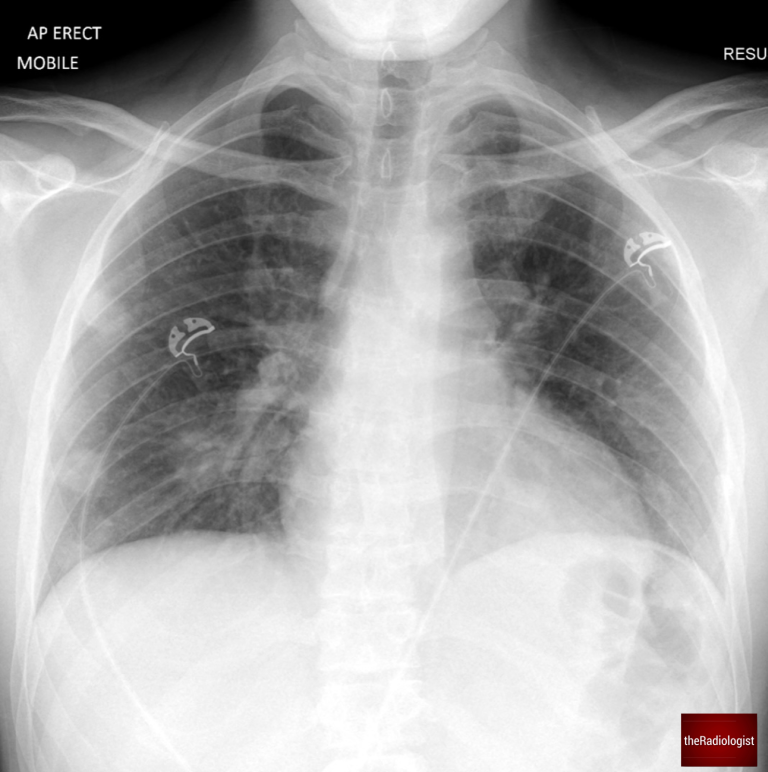

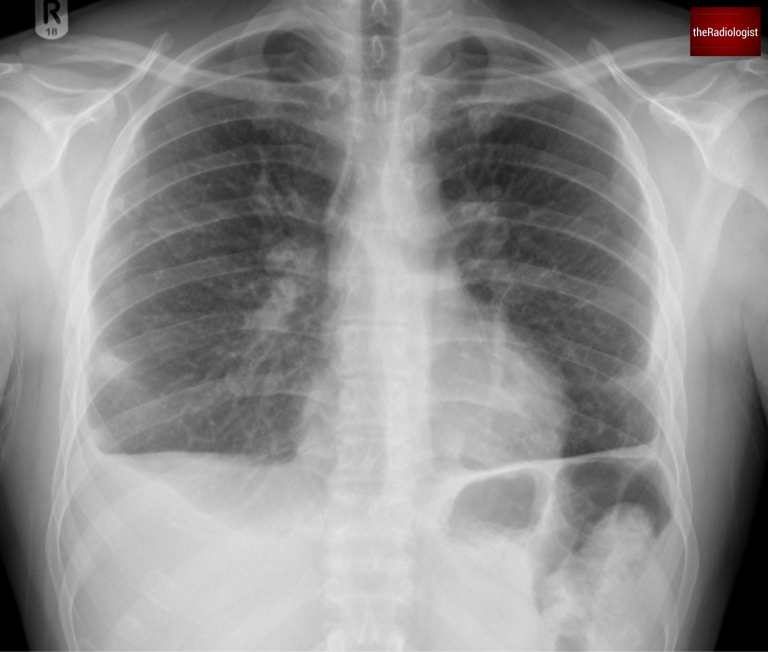

A male in his 20s presents to the emergency department with fever, cough, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain. An anterior-posterior (AP) chest X-ray was performed in ED – we already know by the fact this is AP that the patient is unlikely to be unwell.

AP Chest X-Ray of a male in his 20s

Video explanation

Here is a video explanation of this case: click full screen in the bottom right corner to make it big. If you prefer though I go through this in the text explanation below.

Case findings

The chest X-ray shows several nodules in the right lung, predominantly in the middle and lower zones.

Note that these nodules are notably peripheral, with no evidence of pleural effusion.

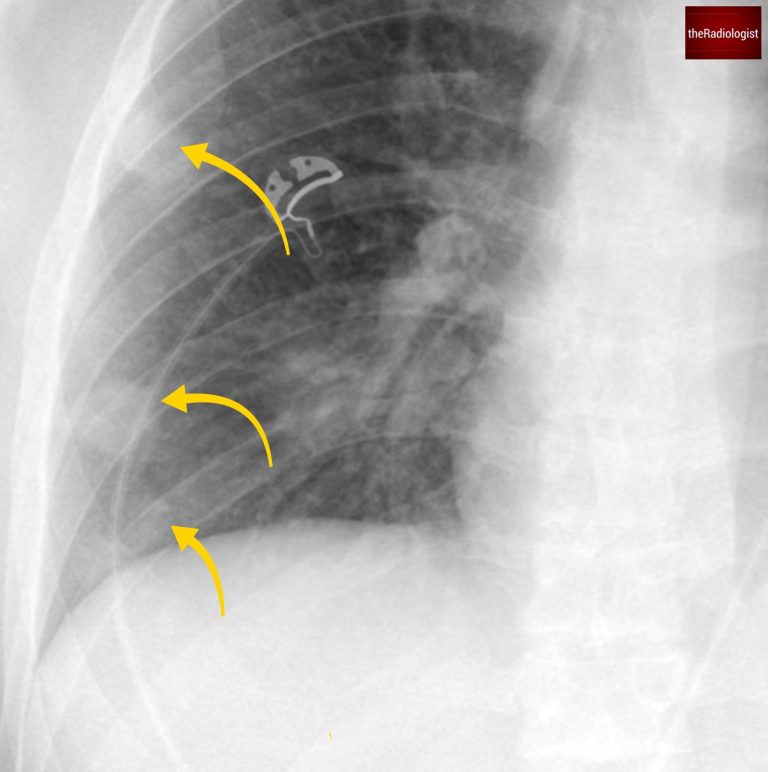

There are several peripheral nodules within the right lung (yellow arrow). There are further nodules seen centrally overlying the hilar vessels in addtion.

Differential diagnosis

In young, acutely ill patients, the differential for multiple lung nodules includes:

1. Septic emboli

- Caused by an infection elsewhere in the body that embolises to the lungs via the pulmonary arteries.

- Characterised by:

- Small, possibly cavitating peripheral nodules

- Peripheral, wedge-shaped opacities due to lung infarction

- Pulmonary arteries often appear normal on imaging, distinguishing this from standard pulmonary embolism (PE).

2. Lung metastases

- Unlikely in this age group but can occur with cancers like testicular tumors or osteosarcoma.

- Clinical presentation rarely matches septic emboli where you’d normally expect a fever and raised inflammatory markers.

3. Granulomatous Polyangiitis (Wegener’s Granulomatosis)

- Can present with nodules, pulmonary hemorrhage, and wedge-shaped opacities.

- Typically associated with haemoptysis.

4. Infection

- Possible, though discrete lung nodules on their own aren’t the usual presentation.

5. Rheumatoid nodules

- Not common in patients under 30

- Can show peripheral nodules but doesn’t fit the clinical picture.

CT scan findings

A subsequent CT scan clarified the findings:

- Peripheral, discrete nodules with cavitation.

- Wedge-shaped areas showing a reverse halo sign (atoll sign), where consolidation surrounds ground-glass opacity.

- A new pleural effusion was noted on the left side.

The reverse halo sign is seen in various conditions but is commonly associated with lung infarction, as seen in septic emboli.

At this stage, septic emboli became the leading differential diagnosis. However, identifying the source of infection was critical to confirm and guide treatment.

There is a wedge shaped region of consolidation and groundglass opacity on the right and a pleural effusion on the left.

Finding the source

Septic emboli originate from infections that spread via the bloodstream. Common sources include:

1. Endocarditis

In particular right-sided endocarditis linked to intravenous drug use. Check for heart murmurs and/or perform an echocardiogram.

2. Thrombophlebitis

Consider indwelling catheters, soft tissue infections and intravenous drug use – examine the groin both physically and on CT.

3. Head and neck infections

Conditions like tonsillitis or pharyngitis can spread to the bloodstream.

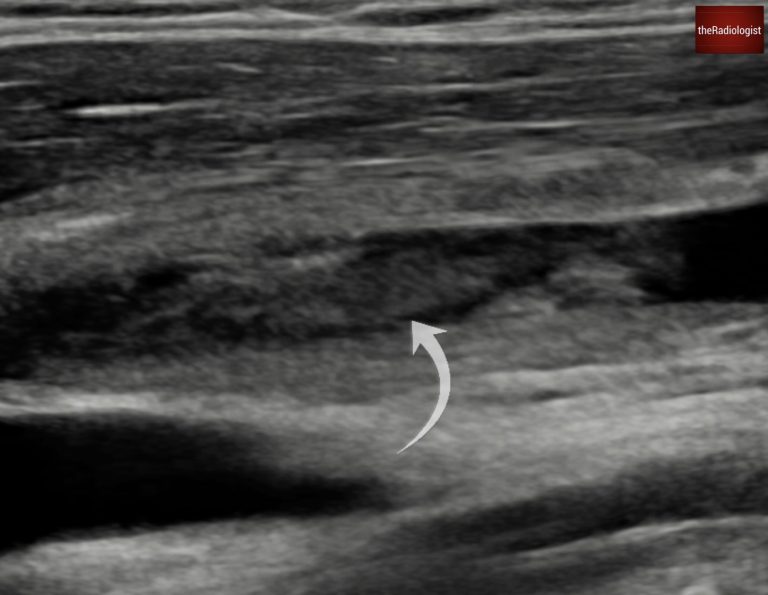

In this case, the patient reported a sore throat one week prior to becoming acutely ill. An ultrasound of the internal jugular vein was performed, revealing a large clot, confirming Lemierre Syndrome.

There is thrombus within the internal jugular vein.

Lemierre syndrome

Lemierre syndrome is a condition where an infection (commonly bacterial) in the head or neck, such as pharyngitis or tonsillitis, causes thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein. Fusobacterium necrophorum (a Gram negative bacillus) is responsible for the majority of infections.

This can result in septicaemia and septic emboli within the lungs and large joints, and can result in in high mortality if untreated. Treatment strategy usually involves intravenous antibiotics and anticoagulation.

Outcome

The patient’s left pleural effusion was tapped and confirmed to be an empyema, a known complication of septic emboli. Radiologists inserted a chest drain to manage this.

After several weeks of treatment, including chest drains, the patient improved. A follow-up chest X-ray showed almost complete resolution of the lung opacities and pleural effusions.

Interestingly, this patient’s initial presentation included abdominal pain and diarrheoa. While unusual, a small subset of septic emboli cases can present with gastrointestinal symptoms. An abdominal CT performed at the time of diagnosis showed no abnormalities, emphasising the need to correlate symptoms with systemic infection.

A follow up chest X-Ray shows almost complete resolution of the right lung nodules.

KEY POINT

Don’t miss septic emboli!

Peripheral cavitating nodules and wedge shaped opacities should make you think about septic emboli.

Once you see these hunt for a source: consider head and neck infection, endocarditis, soft tissue infections and indwelling devices.