Pulmonary embolism

A killer lurking in plain sight

Introduction

Pulmonary embolism is the third leading cause of cardiovascular death worldwide, behind heart attack and stroke. It’s a critical diagnosis that can be life-saving when caught early and devastating when missed.

This article walks through two real cases to help sharpen your eye for PE on imaging. It shows how to spot signs on chest X-ray, understand what makes or breaks CTPA quality, review key anatomy, and avoid common pitfalls when reporting.

It also covers how to assess for right heart strain, look for signs of chronic disease, and recognise when there may be an underlying malignancy or more rare diagnoses. Whether you’re early in training or more experienced, this guide will help you approach CTPAs more confidently and systematically.

Case one introduction

A male in his 70s presents with chest pain and has a CTPA.

Have a look at the scan below.

I know you want to get going but you may need to wait a few seconds for the scan to load. Tap the first icon on the left to scroll.

Chest X-Ray findings in pulmonary embolism

Chest X-Ray is not diagnostic for PE in any way but is often the first step in patients presenting with breathlessness or chest pain so it is worth thinking about what we would expect to see on chest X-Ray in cases of PE.

1. Normal or non-specific basal atelectasis

In up to 40% of PE cases the chest X-Ray can be completely normal.

2. Wedge shaped peripheral opacity (Hampton’s hump)

From experience this can be seen occasionally – a lung infarct can present as a peripheral nodule or region of consolidation on chest X-Ray.

3. Pleural effusion

This will usually be unilateral and small. Not common for a PE presenting with a large effusion.

4. Enlarged pulmonary artery

When enlarged at the hilum can be called a ‘Fleischner sign’. The pulmonary artery becomes expanded with clot and can be seen on chest X-Ray.

5. Oligaemia (Westermark’s sign)

Not that common but you would see a focal region of lucency within the lung.

CTPA technical factors

Let’s think about how to adequately perform a CTPA. We are looking for filling defects within the pulmonary arterial tree so need to be able to opacify these well whilst avoiding breathing artefact.

Even slight movement of the pulmonary arteries can bring about false positives whilst not opacifying the pulmonary arteries well enough can reduce the sensitivity of the scan and lead to missed pulmonary emboli.

Some advocate checking the opacification of the pulmonary trunk by checking the density and ensuring this measures more than 210 Hounsfield units. This is easy to do on most PACS systems by measuring a region of interest. Although this is useful don’t forget to look at the more distal pulmonary arteries and checking whether these are opacified and do not suffer with breathing artefact.

Contrast injection

How do we make sure the pulmonary arteries are well opacified? Firstly we need to time the contrast bolus appropriately usually using one of two techniques:

- Test bolus: a small amount of contrast is injected and we see how long it takes to achieve peak enhancement of the pulmonary trunk then try and replicate that after injecting the full bolus.

- Bolus tracking: place a region of interest (ROI) over the pulmonary trunk and inject the contrast then tell the machine to start scanning when the contrast level reaches a pre-determined threshold.

How should we inject the contrast?

- We need a higher flow rate, usually more than 4 ml/s.

- This usually needs a larger bore cannula – usually 20G or larger although 22G cannulas have been used successfully.

Breathing instructions

Also remember to give the patient the right breathing instructions! A moderate breath hold (gentle inspiration and hold) rather than a forceful maximal inspiration works better as too deep a breath can increase venous return to the heart from the IVC bringing in unopacified blood.

For this reason coaching the patient and practicing the breath hold before the scan can help maximise the opacification of the pulmonary arteries.

KEY POINT

Coaching the patient beforehand with an emphasis on a moderate breath hold rather than a deep forceful breath can help avoid introducing unopacified blood into the pulmonary arteries and help optimise the quality of the scan.

In general practicing maintaining a breath hold before the scan can help avoid breathing artefact.

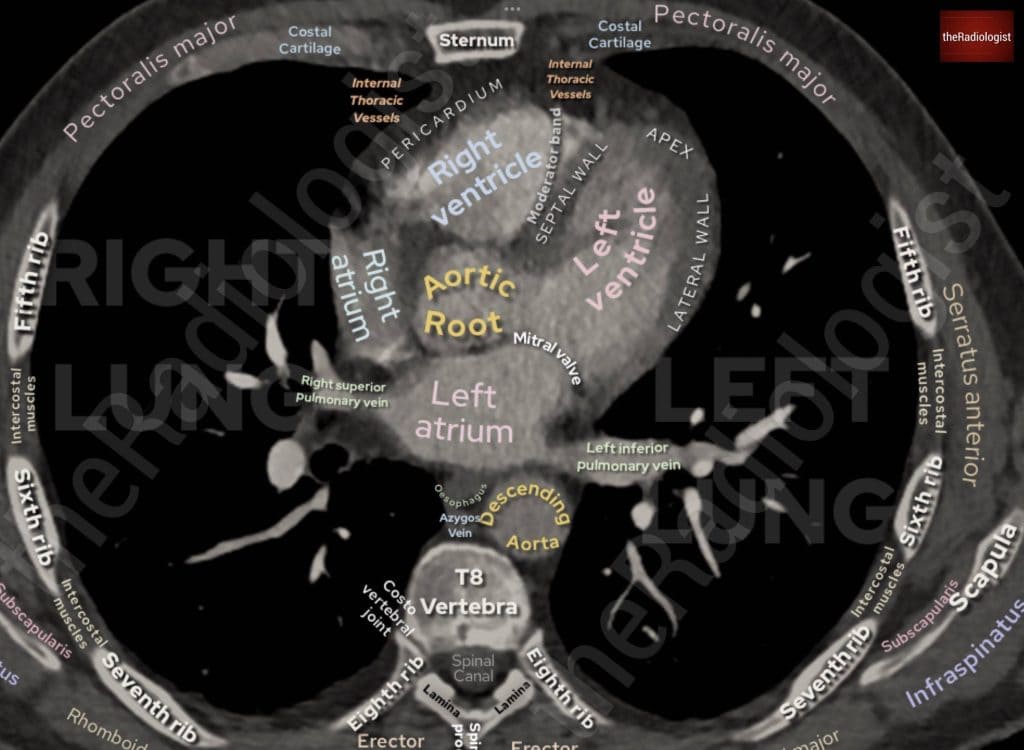

Anatomy review

Now let’s have a look at the scan and examine some anatomy. In every CT scan I review, I follow the contrast from where it was injected all the way into the heart and beyond. This ensures that I don’t miss anything along the way and also helps me identify pulmonary embolism (PE) on scans when we weren’t specifically looking for it (missing a PE is something you don’t want to do at any time as it can be a life threatening diagnosis).

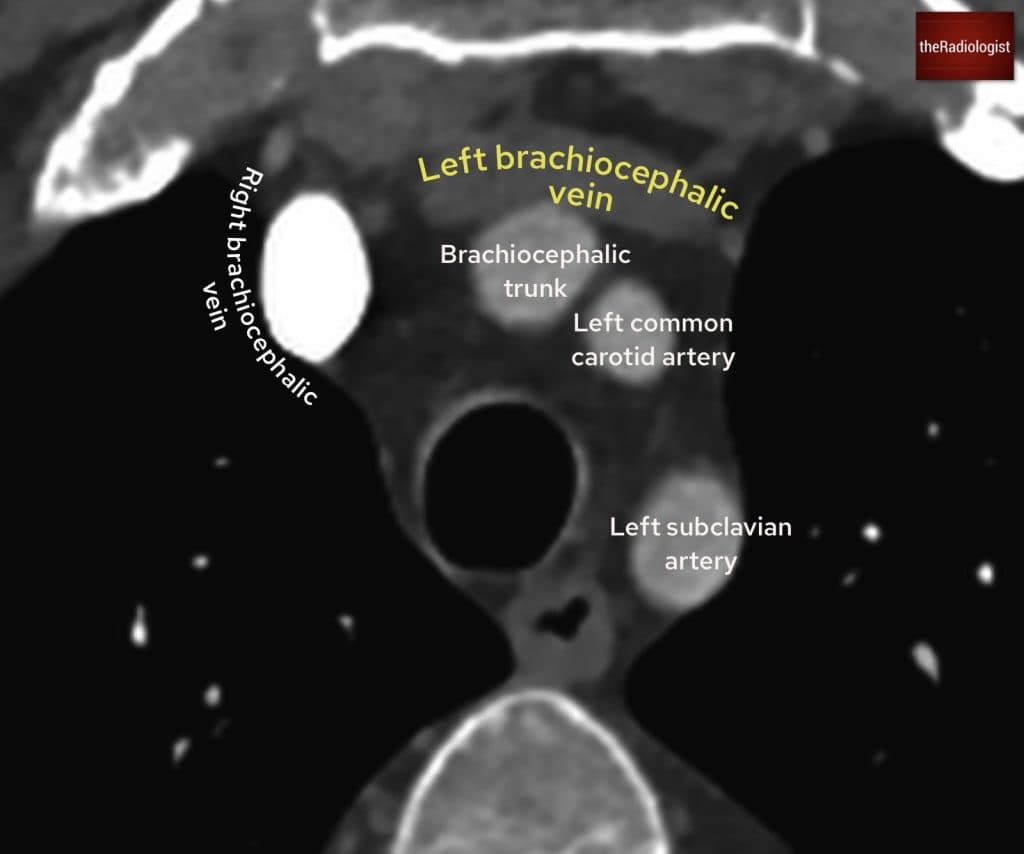

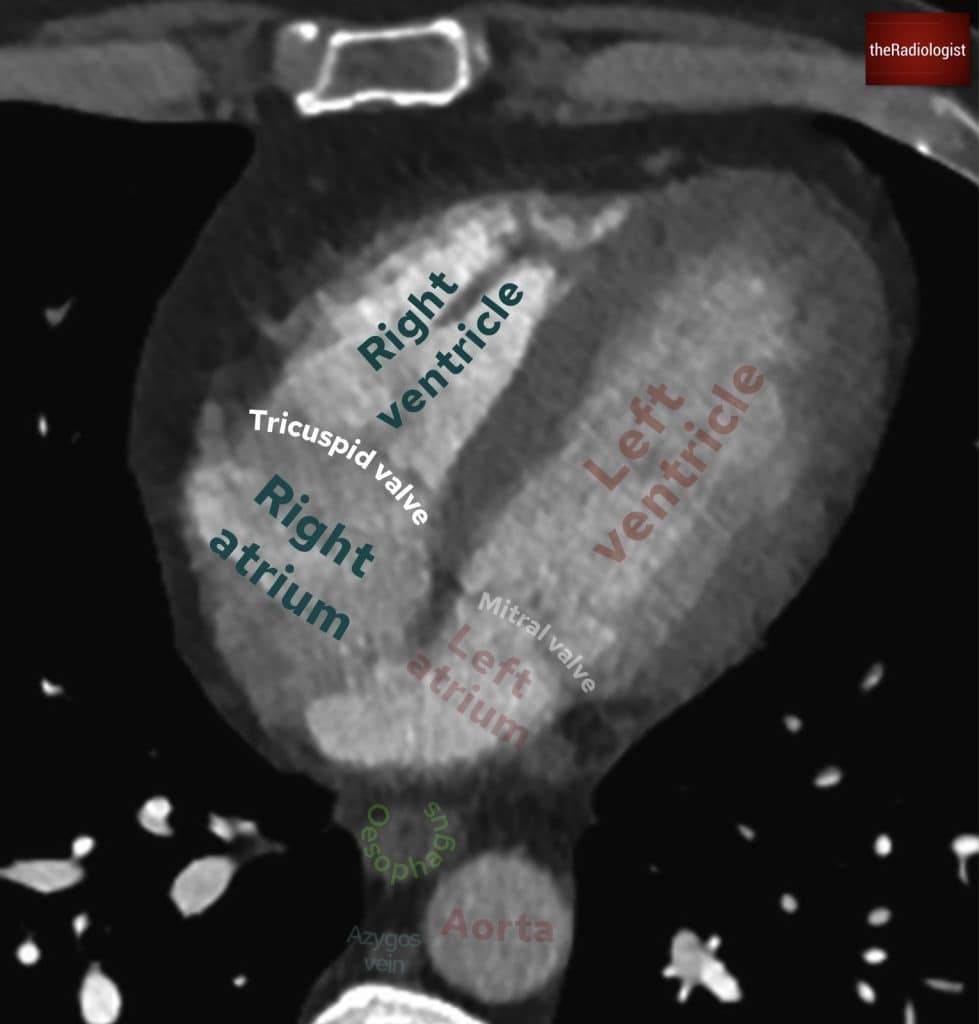

Follow the contrast from the subclavian vein into the brachiocephalic vein on either the left or the right. This will then feed into the superior vena cava and into the right atrium. On a CTPA study, this should appear bright. The contrast will then pass through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle.

Here we see the left and right brachiocephalic veins at the level of the branches of the arch of aorta.

Follow the brachiocephalic veins into SVC and then down into the right atrium. From here you can follow the contrast through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle.

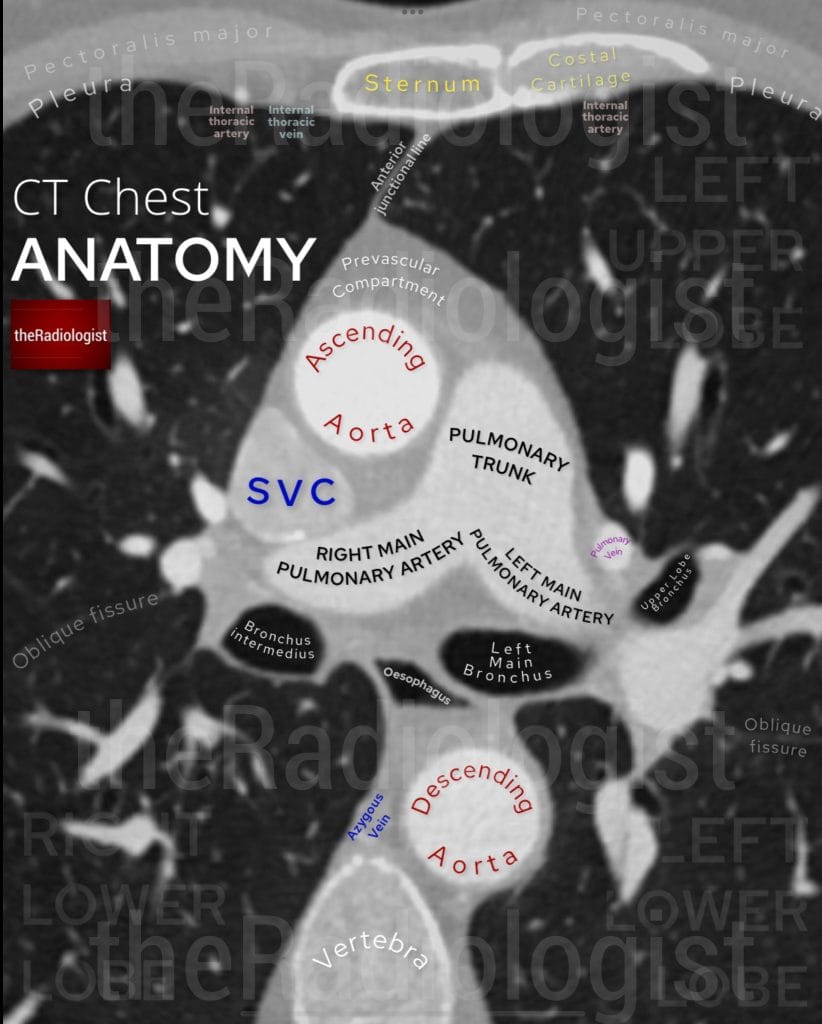

Follow the contrast up into the pulmonary trunk, which will split into two. I like to think this resembles an octopus with many flapping arms, although there are two main arms: the right pulmonary artery and the left pulmonary artery. It is then a matter of following these branches out into each lobe of the lung, and I prefer to zoom in when I do this. This just ensures each artery has not been missed.

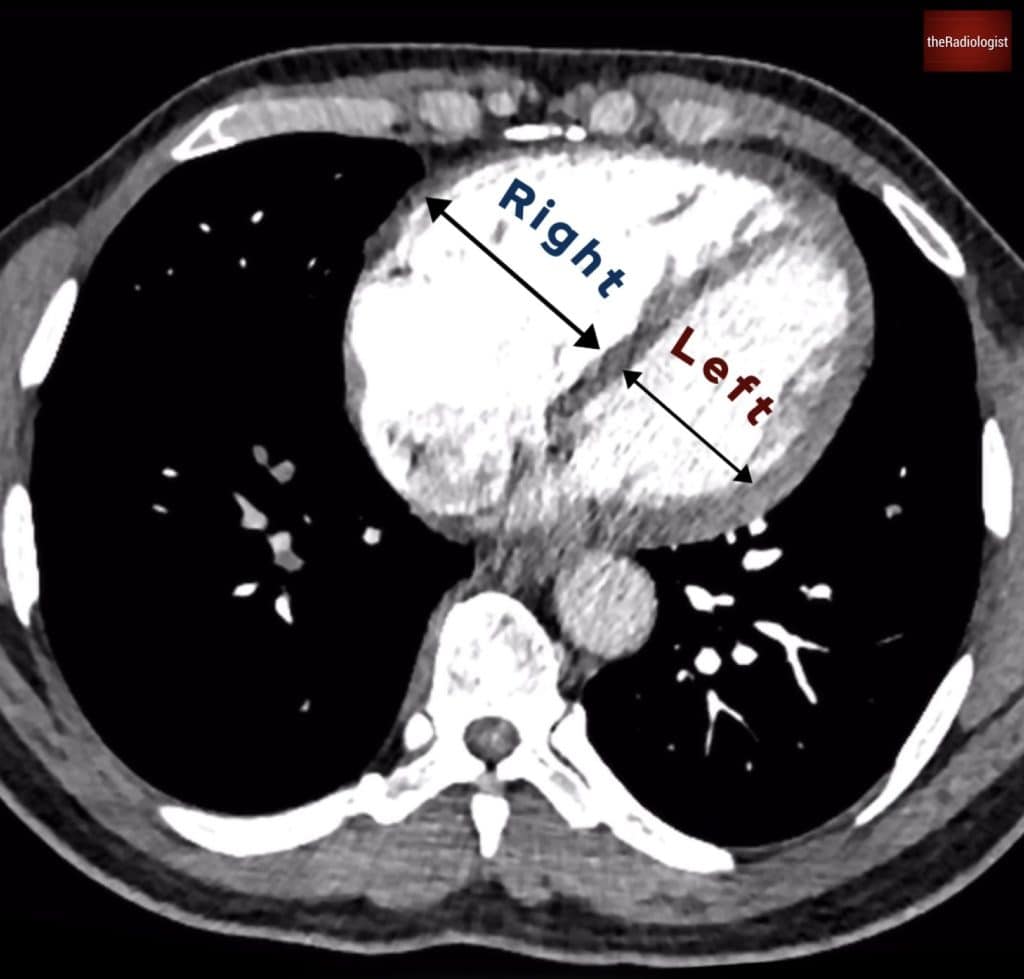

Have a look at this annotated view of a CT chest at the level of the division of the pulmonary trunk, showing the anatomy of the right and left main pulmonary artery.

You are looking for filling defects that could indicate acute PE. Typically, with acute PE, you will observe something called a “polo sign,” where there is a filling defect in the middle of the vessel with contrast surrounding it. This differs from chronic thromboembolic disease, where you may see muralised filling defects on the edges of vessels. Other signs may include webs, thin lines traversing the pulmonary arteries, as well as occluded pulmonary arteries.

Now, follow the contrast all the way out into the pulmonary arteries and then back into the pulmonary veins, which lead into the left atrium, through the mitral valve into the left ventricle, and then up into the aorta.

Annotated view of a CT chest showing the pulmonary veins draining into the left atrium.

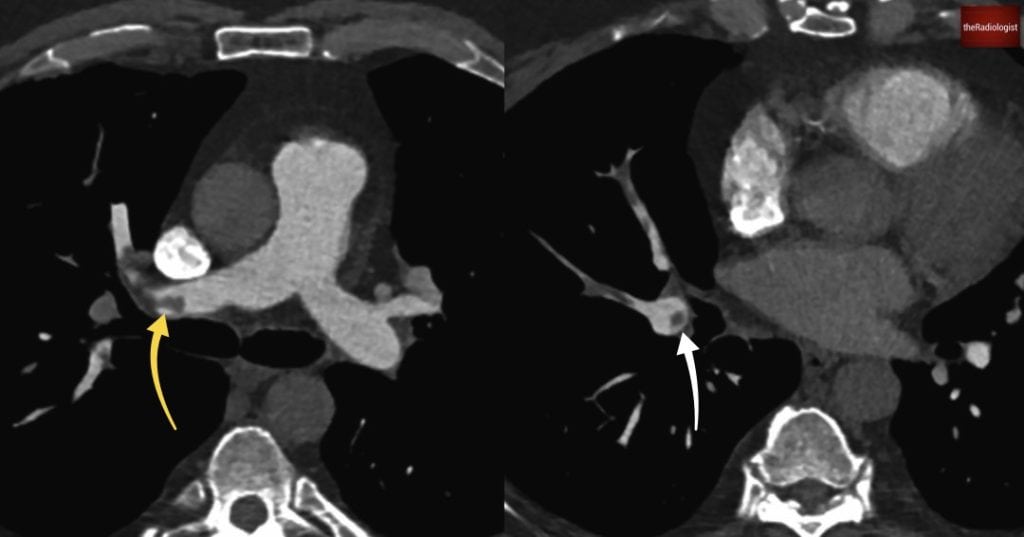

Scan findings

Now let’s look at the scan findings. If we follow the pulmonary arteries in this case, we’ll see that there are filling defects within the right main pulmonary artery. This extends into the right upper lobe pulmonary artery. This extends into all three right sided lobes, and we can see in some areas we have our polo sign, where we have a filling defect and contrast around this. Polo refers to the mint not the horse game (other mints are also available) and this sign suggests acute pulmonary emboli.

We can see in our case there are filling defects within the pulmonary arteries. On the left image there is a filling defect within the right main pulmonary artery (yellow arrow). Going into the right lower lobe on the right hand image we can see a ‘polo sign’ (white arrow) suggesting the pulmonary emboli are acute.

Tips on reviewing a CTPA

Here are some tips that have helped me review CT pulmonary angiograms over the years.

1. Start with the lung parenchyma and secondary signs

Before diving into the vessels, I begin by assessing the lung windows for secondary signs of pulmonary embolism. These include:

- Peripheral opacities (especially with a reverse halo sign, suggesting infarction)

- Pleural effusion

- Atelectasis

If I spot a peripheral opacity with a reverse halo, I consider PE highly likely and focus in on the pulmonary arteries on that bit of lung. In the context of acute chest pain if you see a ‘reverse halo’ sign then it then becomes a case of PE till proven otherwise.

2. Adjust windowing

Window settings are crucial. Avoid using very high contrast or “harsh” windows where the pulmonary arteries are very bright, which can obscure low-attenuation filling defects. Instead, soften the window and level settings so you can clearly appreciate subtle intraluminal contrast defects.

3. Trace each pulmonary artery carefully

One common pitfall is failing to follow each pulmonary artery branch to its corresponding lobe.

For example, I have seen cases where people have missed occlusion of a right middle lobe pulmonary artery. I also review whilst windowing to just be able to see the lung parenchyma simultaneously: this helps confirm that I haven’t missed a pulmonary artery that is occluded. In the context of an occluded pulmonary artery, also remember a peripheral opacity could represent a lung infarct so if you see a peripheral lung nodule trace the pulmonary artery proximal to this.

4. Recognise contrast mixing

In patients with poor cardiac output, right heart strain, or dilated pulmonary arteries, you may see contrast mixing: a swirling appearance of contrast and unopacified blood, often in the central pulmonary arteries.

This can mimic non-occlusive thrombus. To reduce this risk you can try using slower injection rates or considering a split bolus technique.

5. Recognise breathing artefact

Breathing artefact can cause apparent filling defects within the pulmonary arterial tree and can be overcalled as a PE. Putting the scan on lung windows can help recognise if what you are looking at is actually breathing artefact – be careful about overcalling this.

5. Use dual-energy CT if available

Some scanners have the ability to perform dual-energy CT (DECT). This captures images at two different X-ray energy levels, allowing better tissue characterisation than standard CT. In CTPA, it enables generation of iodine maps to assess lung perfusion, aiding in the detection of subtle or peripheral pulmonary emboli.

By spotting the areas of lung on the iodine map that have reduced perfusion, this can guide you to emboli that may otherwise be overlooked.

However, note that:

- It offers a static snapshot of perfusion and is not dynamic like a V/Q scan

- It can help hone your review but shouldn’t replace thorough inspection of the arterial tree

Review areas in positive cases

Great you’ve found a PE but don’t stop there, what things should you then be looking for?

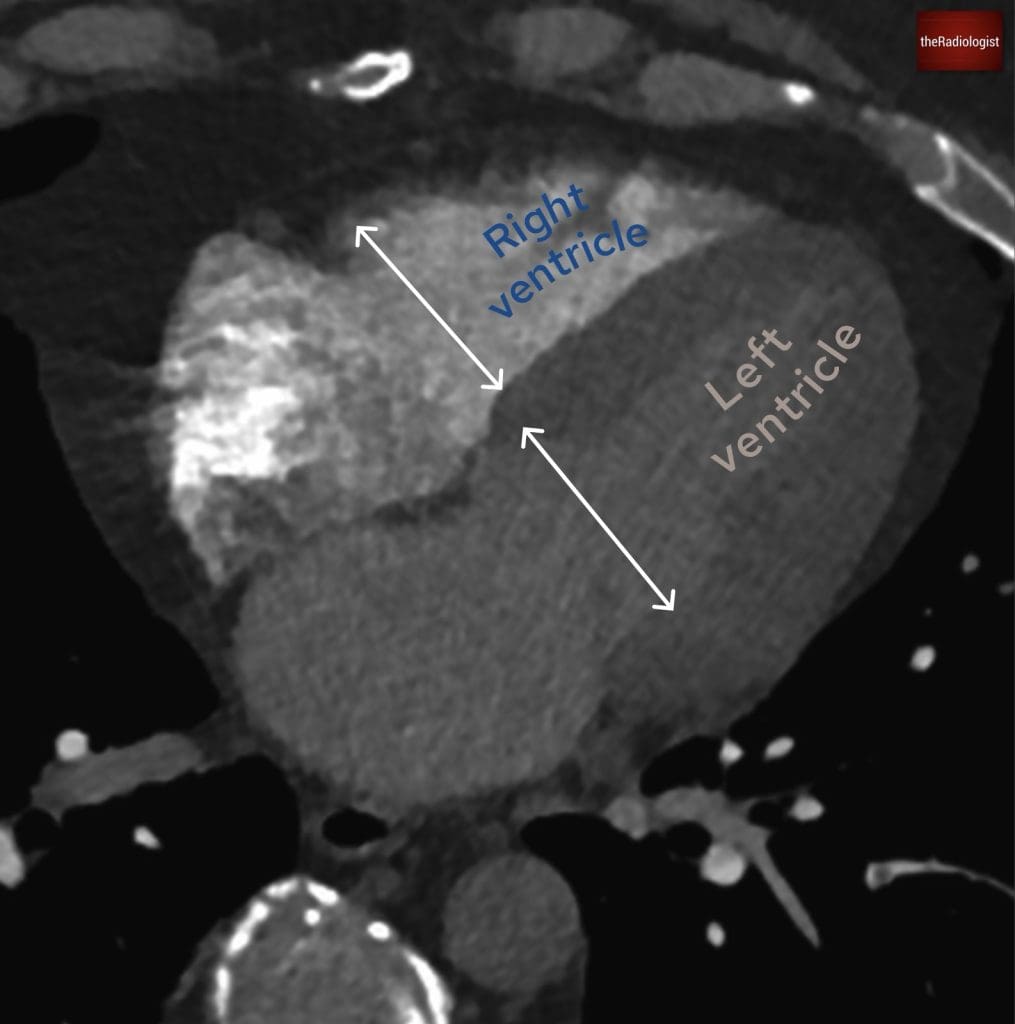

1. Right heart strain

One of the most important aspects of reviewing a CTPA is identifying signs of right heart strain. The RV/LV diameter ratio is key: an RV larger than the LV suggests raised right-sided pressures. To measure this:

- Measure the inner borders of the ventricles (endocardium)

- Does not have to be on the same slice

- Measure in the basal third closest to the valve

This is the key finding and what correlates better with Echo findings and morbity/mortality than signs like septal bowing or reflux of contrast which I like to consider signs that can support a diagnosis of right heart strain on CT. An RV/LV axial dimension ratio of >1 is abnormal and usually can be attributed to the current episode but worth bearing in mind:

- Review previous scans to see if the finding is acute

- Small subsegmental PE is less likely to cause acute right heart strain than a proximal PE

In our case (case one) the right and left ventricle have similar dimensions with no signs of right heart strain.

In case one if we compare the right and left ventricle they have similar dimensions with an RV:LV axial dimension ratio of 1, meaning we cannot call right heart strain.

2. Evaluate for chronic thromboembolic disease

It’s also essential to assess for signs of chronic thromboembolism, which can be subtle but significant.

Chronic PE often presents with eccentric filling defects, wall-adherent thrombus, and web-like structures within the pulmonary arteries. Segmental arteries may appear truncated or reduced in calibre. A mosaic perfusion pattern on lung windows can reflect regional hypoperfusion.

In cases where chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is developing, the pulmonary trunk may be significantly dilated, more than 3 cm and often larger than the ascending aorta. Recognising these features is important for long-term management and referral to specialist centres for further workup, including V/Q scanning and/or right heart catheterisation.

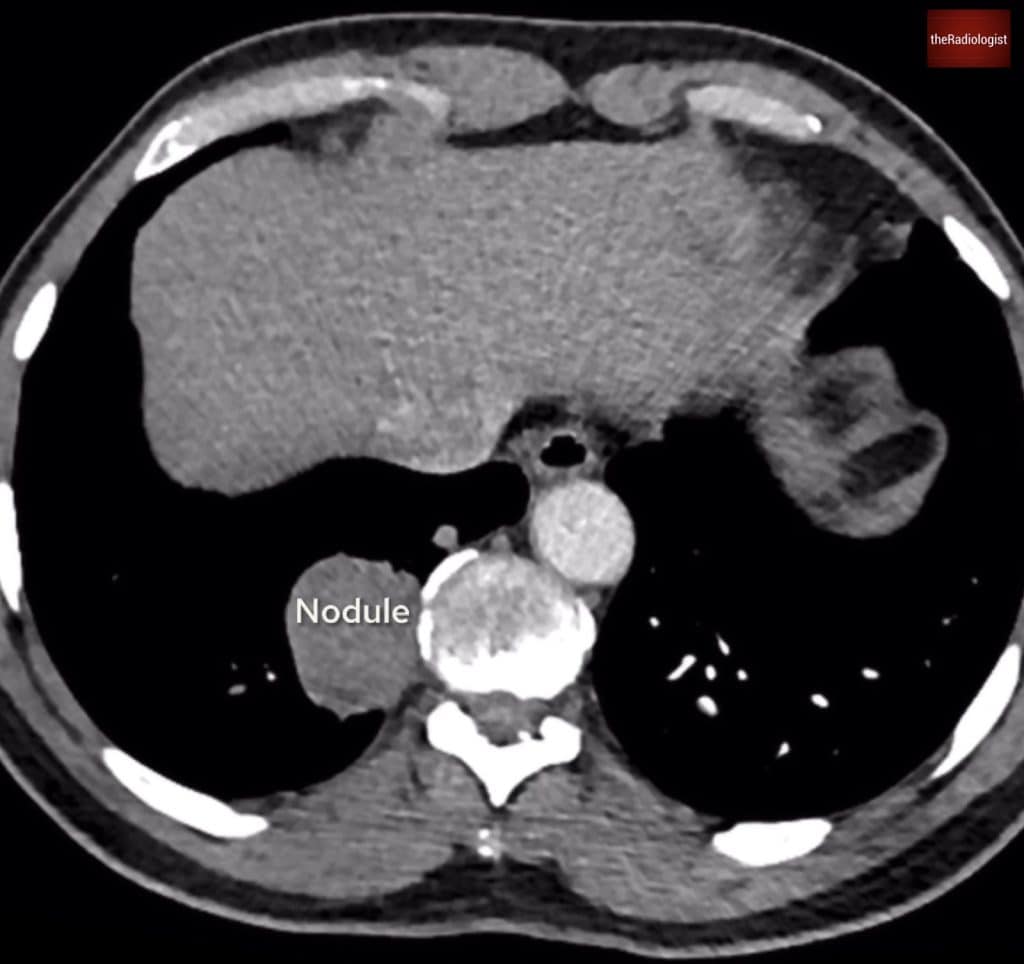

2. Searching for underlying malignancy

Finally, it’s important not to overlook the bigger picture. PE is frequently provoked, and in many cases, malignancy is the underlying driver. A thorough review of the lung parenchyma is essential, particularly for masses or nodules that might suggest a primary lung tumour or metastatic disease.

Equally, reviewing the upper abdominal cuts can sometimes reveal previously undiagnosed malignancies, including pancreatic, adrenal, or hepatic lesions.

Case two introduction

In the next case, we’re presented with a patient in his 70s who had been experiencing progressive breathlessness and unintentional weight loss for several months.

He eventually presented to the Emergency Department, where a CTPA was performed to investigate for pulmonary embolism.

Have a look at the scan below. I know you want to get going but you may need to wait a few seconds for the scan to load. Tap the first icon on the left to scroll.

Video explanation

Here is a video explanation of case two: click full screen in the bottom right corner to make it big. If you prefer though I go through this in the text explanation below.

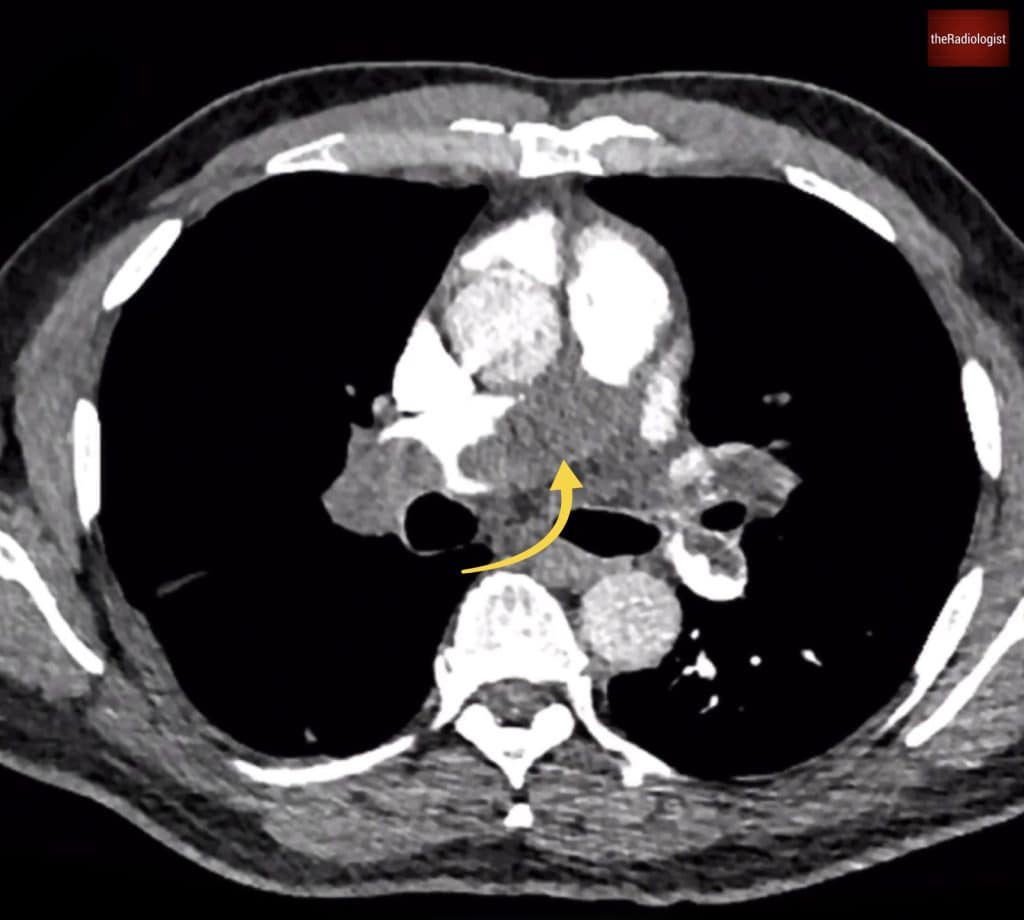

Case two findings

At first glance, the diagnosis seems straightforward: the scan shows extensive central pulmonary artery filling defects, with large filling defects involving the pulmonary trunk, right, and left main pulmonary arteries. Once we see this let’s go through our review areas.

We can see extensive pulmonary artery filling defects within the pulmonary trunk (yellow arrow) extending into both main pulmonary arteries.

Right heart strain

Signs of right heart strain appear present, with namely an enlarged RV as well as a flattened interventricular septum, and reflux of contrast: all of which raise concern for significant haemodynamic impact. As discussed earlier, these findings correlate with increased 30-day mortality and inform how aggressively the patient might need to be treated.

In this case the RV/LV axial dimension ratio is >1 and we can call right heart strain.

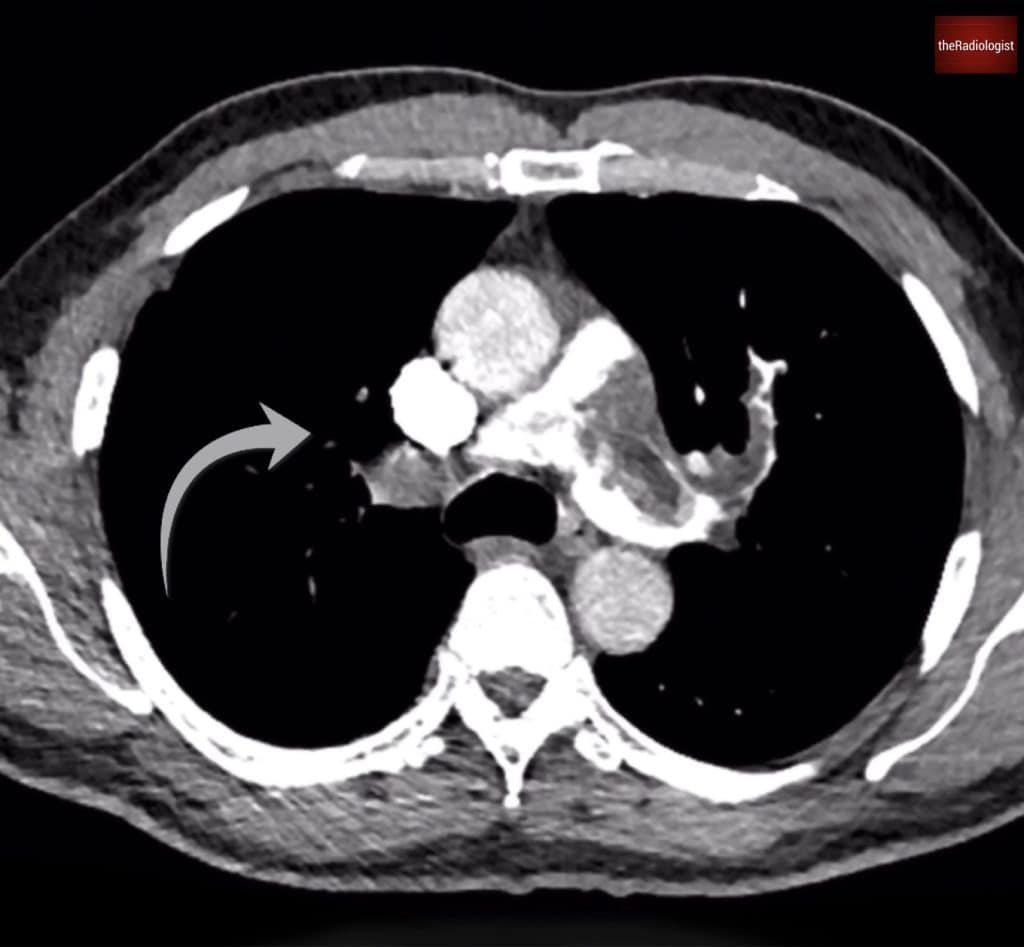

Chronic features

However, there are also signs suggesting a chronic component. Some segmental arteries, particularly on the right, appear of reduced calibre or are occluded. These findings shift the differential towards chronic thromboembolic disease.

Pulmonary arteries within the right upper lobe are of reduced calibre suggesting chronic thromboembolic disease.

Underlying malignancy

Have a look at lung windows and there are multiple pulmonary nodules, the largest located in the right lower lobe. The upper abdominal cuts were unremarkable, but the presence of multiple nodules raise concern for metastatic disease.

There are multiple lung nodules with the largest within the right lower lobe.

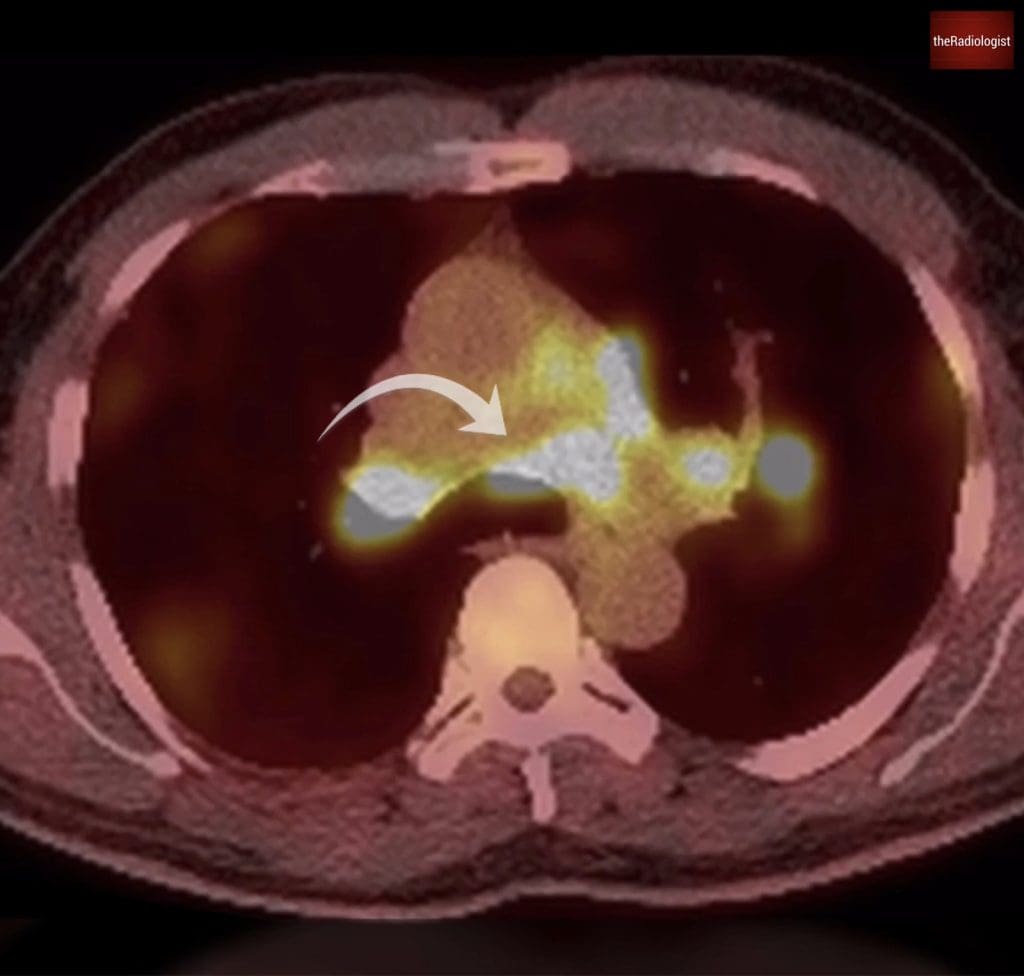

Further workup with PET-CT

A subsequent PET-CT added a surprising layer: not only were some of the lung nodules FDG-avid, but the pulmonary artery filling defects themselves were also avid, something we wouldn’t expect in typical thromboembolic disease. Normally, thrombus is non-avid on PET imaging.

PET-CT shows interestingly the pulmonary artery filling defects are FDG avid.

Rethinking the diagnosis

This finding prompted a reconsideration of the diagnosis. While rare, pulmonary artery tumour embolism and pulmonary artery sarcoma must be considered when intravascular filling defects demonstrate metabolic activity on PET. These have been described in association with metastatic spread from tumours such as renal cell carcinoma, osteosarcoma, and even atrial myxoma.

In this case, a biopsy of the lung nodules suggested an underlying sarcoma, leading to the working diagnosis of a primary pulmonary artery sarcoma: an uncommon and often missed entity that can closely mimic acute or chronic PE. Typically arising from the pulmonary trunk, these tumours often fill and expand the lumen, giving the appearance of a massive central embolus. Enhancement on post-gadolinium MRI, and avid PET uptake, help distinguish sarcoma from thrombus.

CT guided lung biopsy of the right lower lobe nodule suggested a sarcoma leading to a working diagnosis of a primary pulmonary artery sarcoma.

Outcome

Unfortunately, the prognosis is generally poor due to delayed diagnosis and significant vascular obstruction by the time of presentation. Some patients may be eligible for surgical resection, often combined with adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy, but treatment is complex and outcomes vary.

KEY POINT

Whenever you find a pulmonary embolism it is important to focus your review on right heart strain, signs of chronic thromboembolic disease and signs of underlying malignancy.