Psoas abscess

On abdominal CT and MRI

Introduction

Psoas abscesses are easy to miss if you’re not actively looking for them. In this case, we review how to spot key signs on CT and MRI, highlight the importance of checking the psoas muscles, and show the role of follow-up imaging in monitoring treatment response.

A useful case to sharpen your search pattern on abdominal CT and understand why MRI is the gold standard for assessing spondylodiscitis.

Case introduction

A male in his 50s presents to the ED with back and abdominal pain as well as a fever. He has a post contrast CT of his abdomen and pelvis in a portovenous phase.

Have a look at the scan below.

I know you want to get going but you may need to wait a few seconds for the scan to load. Tap the first icon on the left to scroll.

Video explanation

Here is a video explanation of this case: click full screen in the bottom right corner to make it big. If you prefer though I go through this in the text explanation below.

Psoas major muscles

When reviewing abdominal or back pain, always inspect the psoas major muscles. They arise from the lower thoracic and lumbar spine and join with the iliacus, inserting into the femur.

The psoas muscles originate from the vertebral bodies of T12-L4, these intervertebral discs and the transverse processes of L1-L5. It then inserts into the lesser trochanter of the femur as the iliopsoas tendon.

Now let’s have a look at the CT scan above in a bit more detail.

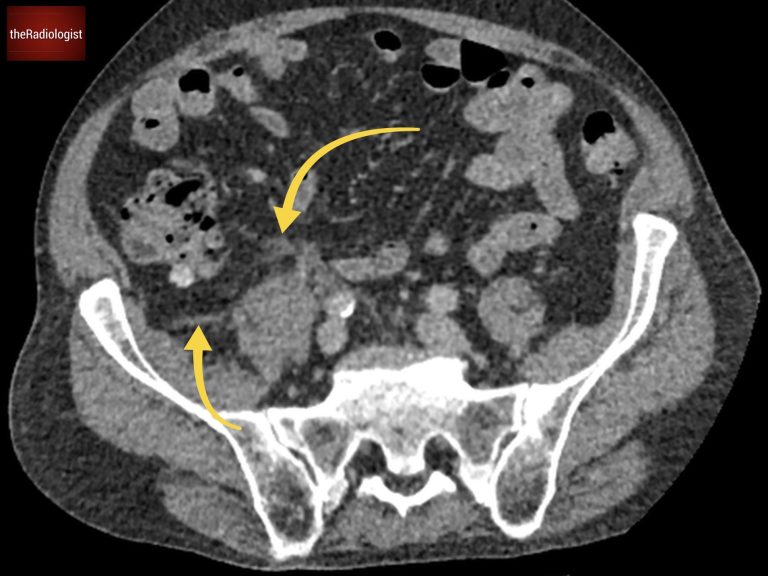

If we look at the psoas muscles which lie on either side of the vertebrae, we can see there is some asymmetry. The right psoas is larger than the left and we’ve lost some of the fat planes within the muscle. This is subtle but make sure you compare the psoas muscles on every CT you look at. They look a bit like Mickey Mouse ears to me so you’re looking to see if the ears are symmetrical.

Compare the psoas muscles side by side. The right sided psoas muscle appears expanded with a loss of its normal fat planes.

Also as we scroll down we can see there is fat stranding surrounding the psoas muscle extending into the pelvis.

There is fat stranding surrounding the psoas extending into the pelvis.

Causes of unilateral psoas enlargement

What are the considerations when we see unilateral psoas enlargement on a CT scan?

1. Psoas abscess

A psoas abscess can develop either primarily (typically in immunosuppressed patients or diabetics) or secondarily from infections in nearby areas like the abdomen or vertebral spine (spondylodiscitis). On CT, a psoas abscess might show peripheral enhancement and fluid density, although these signs aren’t always easy to detect.

2. Psoas haematoma

Haematomas may occur in patients on anticoagulants or with blood disorders, and can also develop due to trauma or a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). Differentiating a haematoma from an abscess can be challenging on CT, but high density within the psoas muscle often suggests a haematoma.

3. Tumour invasion

While tumours can invade the psoas muscle, this is more common as an extension from retroperitoneal cancers. Metastatic disease rather than primary tumours usually accounts for psoas invasion.

MRI scan findings

In this case, the asymmetry and inflammation around the psoas muscle hinted strongly at a psoas abscess. The reporting radiologist picked this up and recommended an MRI to assess the psoas in more detail whilst also looking for a spondylodiscitis.

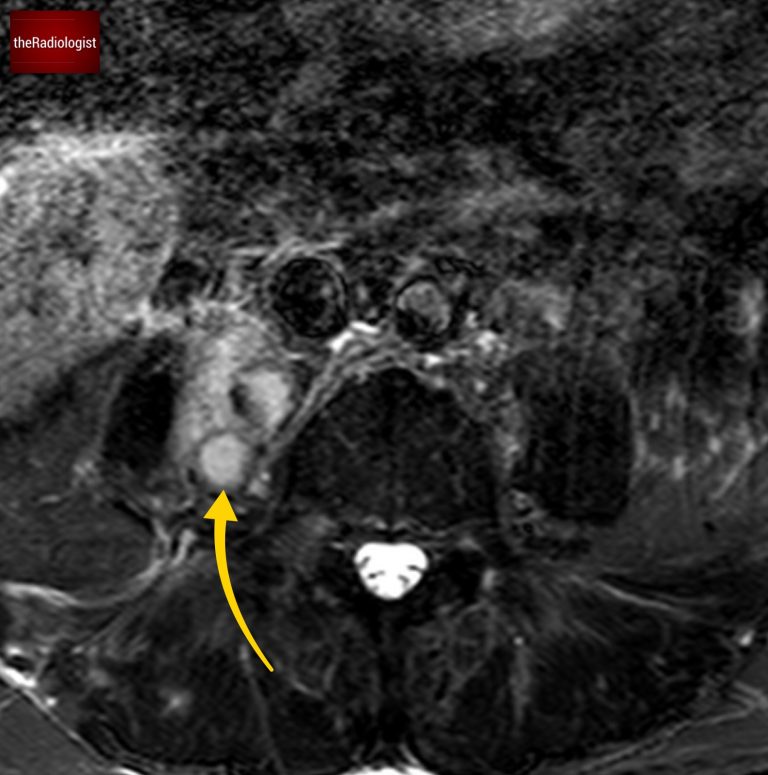

Due to pain the patient could only tolerate a few STIR sequences so we don’t have a complete scan but have a look at this axial STIR sequence below. We have high STIR signal within the right psoas with locules suggesting abscess formation.

Have a look at this axial STIR image from the MRI scan. Here we have high SITR signal within the right psoas with locules suggesting abscess formation.

If we look at a lateral STIR sequence of the lumbar spine, we can see high signal in the lateral aspect of the L3-4 disc which is continuous with the abscess formation within the right psoas. This highly suggests a spondylodiscitis as the primary pathology leading to secondary psoas abscess.

High signal within the lateral aspect of the L3-4 disc is continuous with abscess formation.

These usually present with back pain and typically occur over the age of 50. There may be a history of infection elsewhere whilst things like imunosuppresion, steroid use, diabetes and intravenous drug use can increase the risk. It usually involves a single level but several levels can be involved typically in tuberculous discitis.

The infection usually involves both the vertebral endplate and disc and in adults is thought to arise in the endplate first (hence why ‘spondylodiscitis’ is a preferred term over ‘discitis’).

Although we couldn’t see this on our CT case, irregularity of the endplates can be seen after a few weeks on X-Ray and CT as well as loss of disc space. MRI is more sensitive and we are looking for high T2 or STIR signal within the endplates, disc and paraspinal tissues and psoas muscles. Gadolinium contrast can help as we may see enhancement of the endplates, disc and peripheral enhancement of any abscesses. It’s important on MRI to ensure there is no significant central canal stenosis secondary to abscess formation or vertebral collapse.

DIAGNOSIS

The MRI findings are consistent with a primary spondylodiscitis leading to secondary right sided psoas abscess formation.

Follow up

The patient was treated with a long course of antibiotics and we can see a good response on imaging with improvement in the right psoas abnormality at 2 months.

On a follow up MRI scan 2 months later we can see the right psoas is now returning to normal.

KEY POINTS

Remember to assess the psoas muscles on CT!

Unilateral enlargement with surrounding fat stranding could mean a psoas abscess which may not show well on CT alone and may need MRI to confirm the diagnosis. MRI can also help assess for an underlying spondylodiscitis.