Assessing a pneumothorax

On chest X-Ray and CT

Introduction

A pneumothorax can be tricky to spot but recognising it early on a chest X-ray is crucial for effective treatment.

In this article, we’ll go through the key signs of pneumothorax, how to distinguish it from more serious conditions like a tension pneumothorax, and what to look for when interpreting X-rays.

Understanding these concepts is essential for radiologists, clinicians, and anyone working with chest imaging.

By reading this, you’ll gain the confidence to identify pneumothorax cases accurately and quickly to help improve the care you give to your patients. This guide will provide you with practical insights you can apply directly to your daily work, whether you’re new to radiology or looking to sharpen your skills.

Case introduction

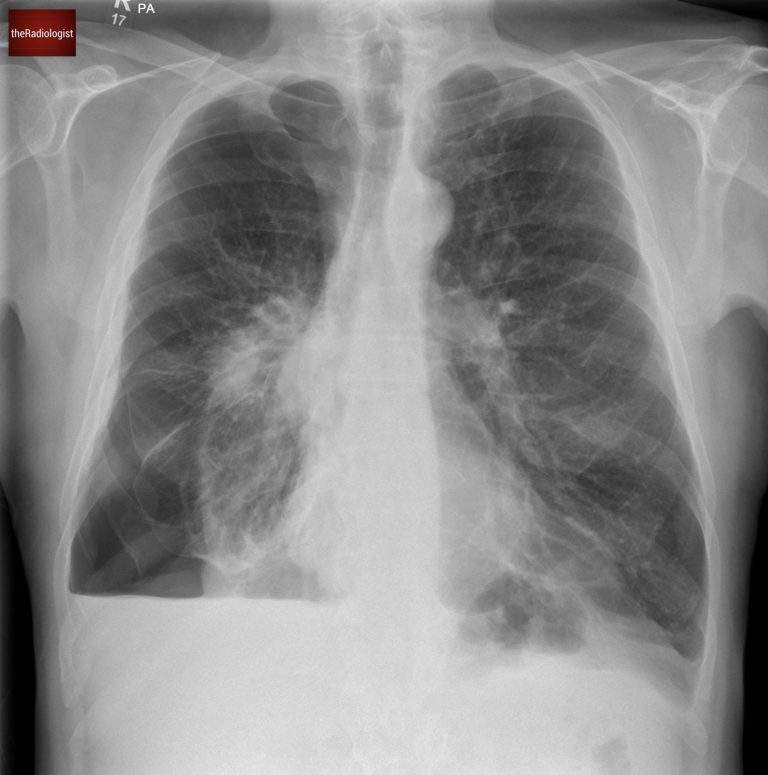

A man in his 50s arrives at the Emergency Department with sudden breathlessness, following a few weeks of a productive cough. A chest X-ray is performed, can you spot the diagnosis?

Let’s break it down step by step.

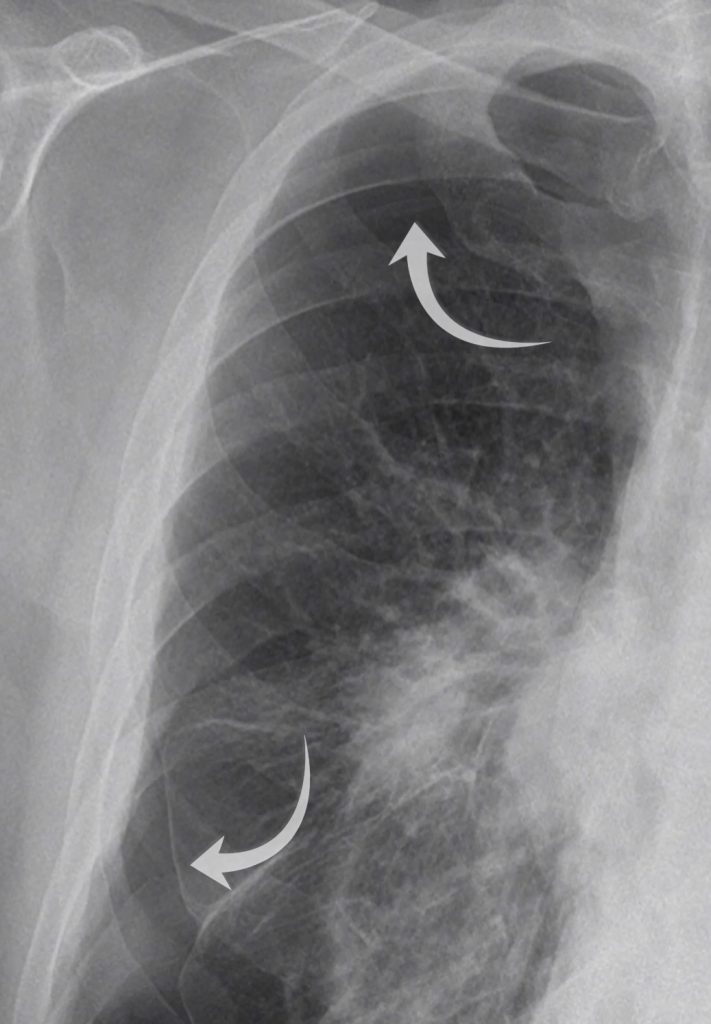

PA view of a chest X-Ray of a male in his 50s

Video explanation

Here is a video explanation of this case: click full screen in the bottom right corner to make it big. If you prefer though I go through this in the text explanation below.

What is a pneumothorax?

Here we have a PA chest X-ray with a lot going on. Did you notice the right-sided pneumothorax?

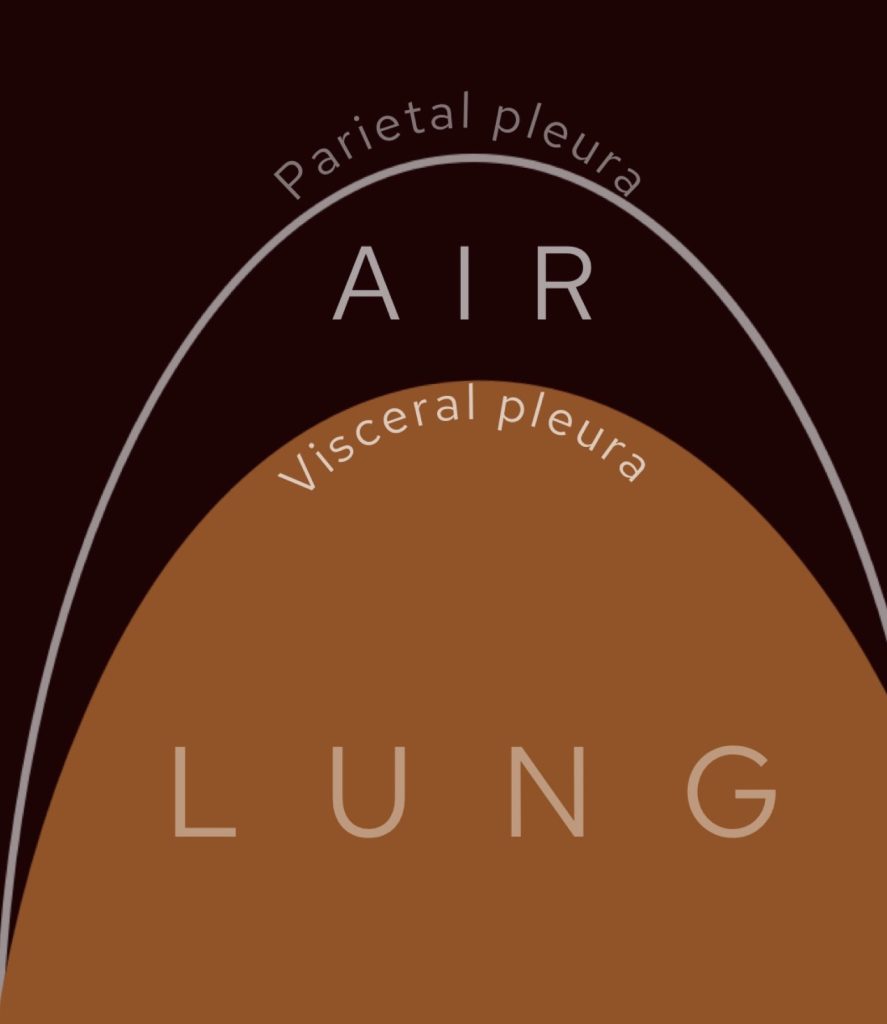

A pneumothorax occurs when air enters the pleural space which is the gap between the visceral and parietal pleura.

In a pneumothorax we find gas between the two layers of the pleura, the visceral and parietal pleura.

Causes

What causes a pneumothorax?

The causes are varied and we can split this up into primary and secondary spontaneous pneumothoraces whilst also thinking about trauma and iatrogenic causes. As a radiologist who has biopsied thousands of lungs I have seen my fair share of iatrogenic pneumothoraces!

| Category | Cause | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous | Primary | Classically affects tall thin young males. Usually due to rupture of subpleural blebs or bullae. |

| Secondary | Affecting someone with underlying lung disease such as: emphysema, interstitial lung disease, connective tissue disorders, cystic lung disease (notably lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis and Birt-Hogg-Dube) or pneumonia. | |

| Trauma | Direct chest trauma | Can be blunt trauma (eg motor vehicle accident usually with rib fractures) or penetrating trauma (such as stab or gunshot wounds). |

| Iatrogenic | Medical procedures | As radiologists we see a lot of these with CT guided lung biopsies with risk increased in the presence of emphysema. Other causes include central line insertion, pacemaker insertion, thoracocentesis and even breast biopsies. |

| Rare | Catamenial pneumothorax | Occurs secondary to thoracic endometriosis and occurs within 72 hours of menstruation onset. |

| Foreign body inhalation | A rare complication. |

Signs of a pneumothorax

What are the key signs of a pneumothorax on chest X-Ray?

- Increased lucency compared to normal lung.

- A thin white pleural line, representing the visceral pleura, with no lung markings beyond it.

In most cases gas will rise to the lung apex and the white pleural line will parallel the chest wall although there are exceptions. Sometimes a pneumothorax can be loculated and seen within the mid and lower zone whilst if an X-Ray is performed supine you may get a ‘deep sulcus sign’ where there is a deepened costophrenic angle which is lucent.

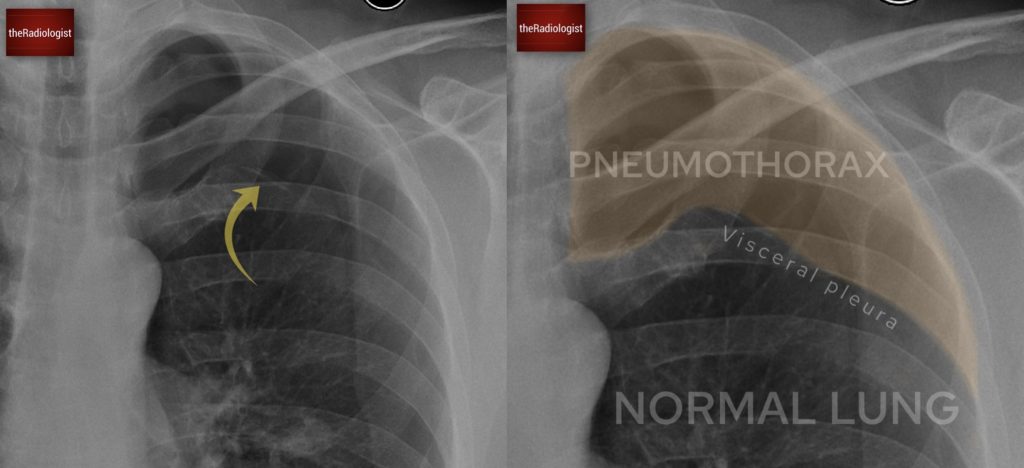

Have a look at this separate case where we can see a white ‘pleural line’ representing the visceral pleura and gas within the pleural space.

In this separate case we can see a thin white pleural line representing the visceral pleura with no lung markings beyond it. This is typical for an apical pneumothorax. If you don’t zoom up you may miss this!

Hydropneumothorax

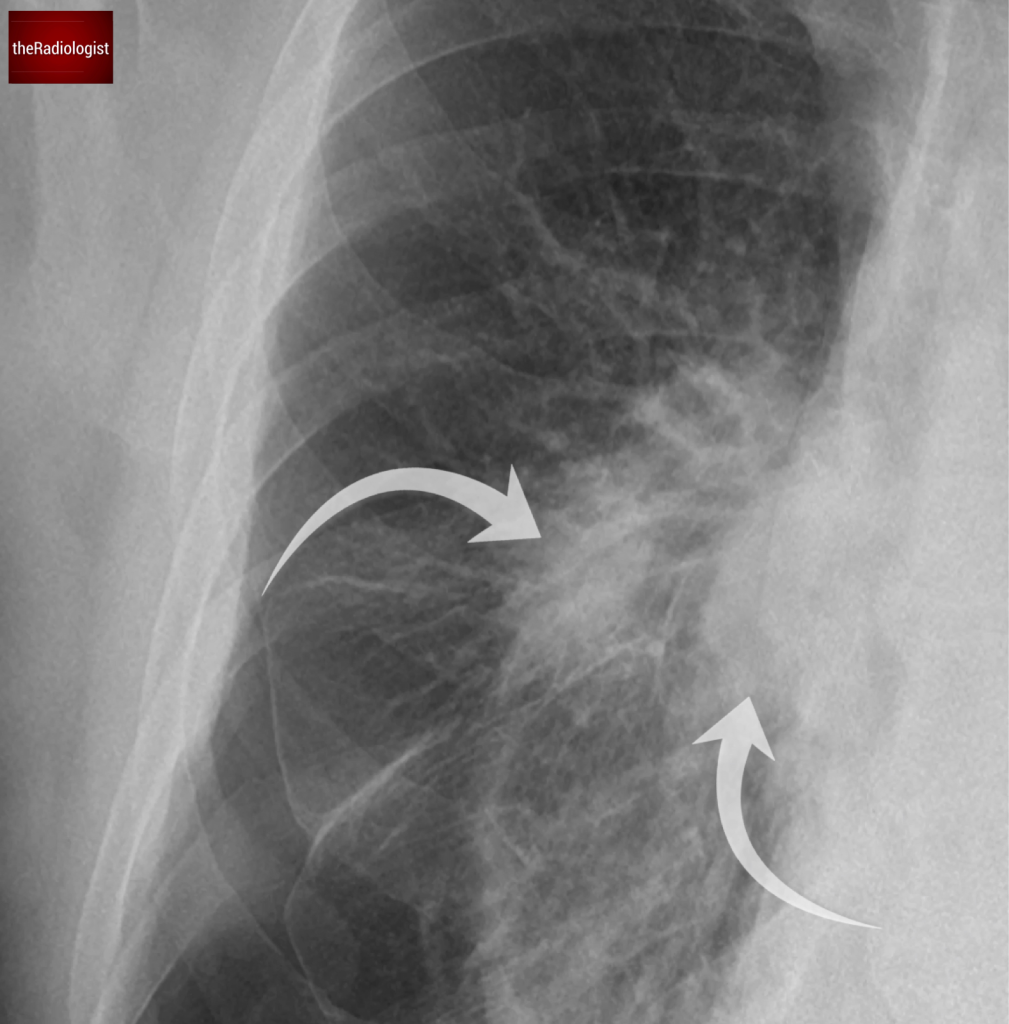

Going back to our case you will see a clear pleural line at the right lung apex whilst there is also a component at the right lung base, which is less commonly seen.

Did you spot the white pleural line both at the apex and within the right lower zone?

We can also see an air-fluid level at the right lung base – this represents a ‘hydropneumothorax’ ie there is both fluid and gas within the pleural space. Note how this appears slightly different to a standard pleural effusion where you get a ‘meniscus sign’ rather than a straight air-fluid level – this is because there is no surface tension from air in a hydropneuomothorax.

With a hydropneumothorax given the lack of surface tension we commonly see an air-fluid level rather than a meniscus sign that we see with a pleural effusion.

Assessing for tension pneumothorax

When evaluating a pneumothorax, always check the X-Ray for signs of a tension pneumothorax. Now ideally this should be suspected clinically before getting to the point of an X-Ray but that doesn’t always happen so we need to know how to look for it.

Tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency where gas gets into the pleural space but can’t get out. This leads to collapse of the lung, pressure on the mediastinum and compression of the major veins ie the SVC. Reduced venous return to the heart leads to reduced cardiac output, arrhythmia and cardiac arrest.

Clinical features include respiratory distress with tracheal deviation away from the affected side with a lack of breath sounds and hyperressonance to percussion. Observations will show low blood pressure, tachypnoea and tachycardia.

So obviously this is something you want to avoid. Treating a tension pneumothorax involves inserting a large bore needle (14G) into the second intercostal space within the midclavicular line and you should hear a hissing sound. Once you’ve done this you’ll want to treat the pneumothrax with a chest drain. If doing this without radiological assistance the classic teaching is to insert this into the 5th intercostal space, mid-axillary line. Remember to always go above ribs to avoid the neurovascular bundle.

Once we see a pneumothorax on X-Ray, how do we assess for tension?

- Mediastinal shift: for a clue I always check to see if some of the heart is to the right of the spine (as long as the film is not rotated). Look at the position of the trachea. If you are unsure about mediastinal shift comparing to old films can help you.

- Flattening of the diaphragm

Remember that tension is unlikely to happen with small apical pneumothoraces.

Now if we look at our case we can see the trachea and mediastinum are central meaning there is no tension pneumothorax.

In our case the trachea is in a normal position with no signs of shift to suggest shift in the context of tension. Note minor deviation of the trachea to the right at the level of the aortic arch is normal.

Assessing for lung lesions

There isn’t just a pneumothorax in this case, the underlying lung looks abnormal. Looking closely we can see a right mid zone opacity and a second opacity behind the right hilum (see the image below).

What could these opacities represent?

While there are multiple possibilities, the most important differentials to consider are:

- Infective consolidation (pneumonia): especially given the patient’s history of a productive cough.

- Lung malignancy: either a primary lung cancer or metastatic deposits.

Look closely and you will find two opacities within the right mid zone, one within the right mid zone and another overlying the right hilum.

CT scan review

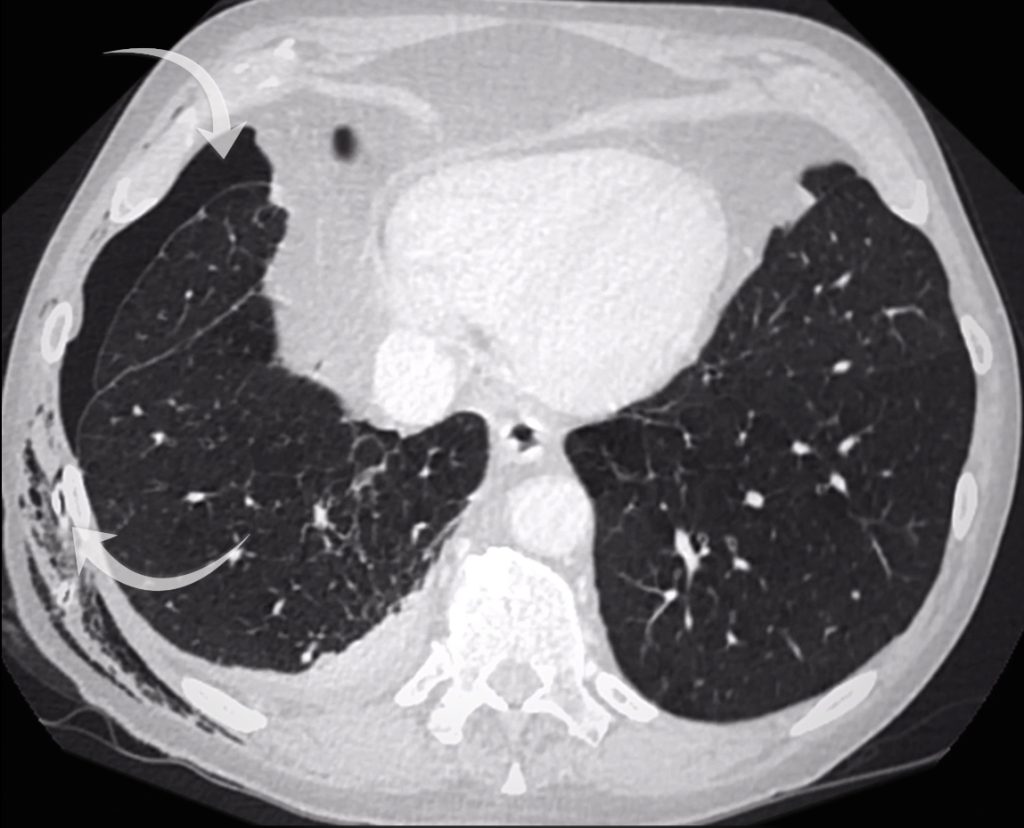

A chest drain was inserted, but the patient’s breathlessness didn’t improve, a red flag suggesting the drain might not be in the right place. Now have a look at the CT scan in this case.

Be sure to have a look at both soft tissue and lung windows (toggle the down arrow, third icon to the left). It may take a second to load.

Let’s go through the findings:

- The chest drain is in the chest wall, not in the pleural space, explaining why the pneumothorax persists.

- There is severe emphysema and a small right pleural effusion.

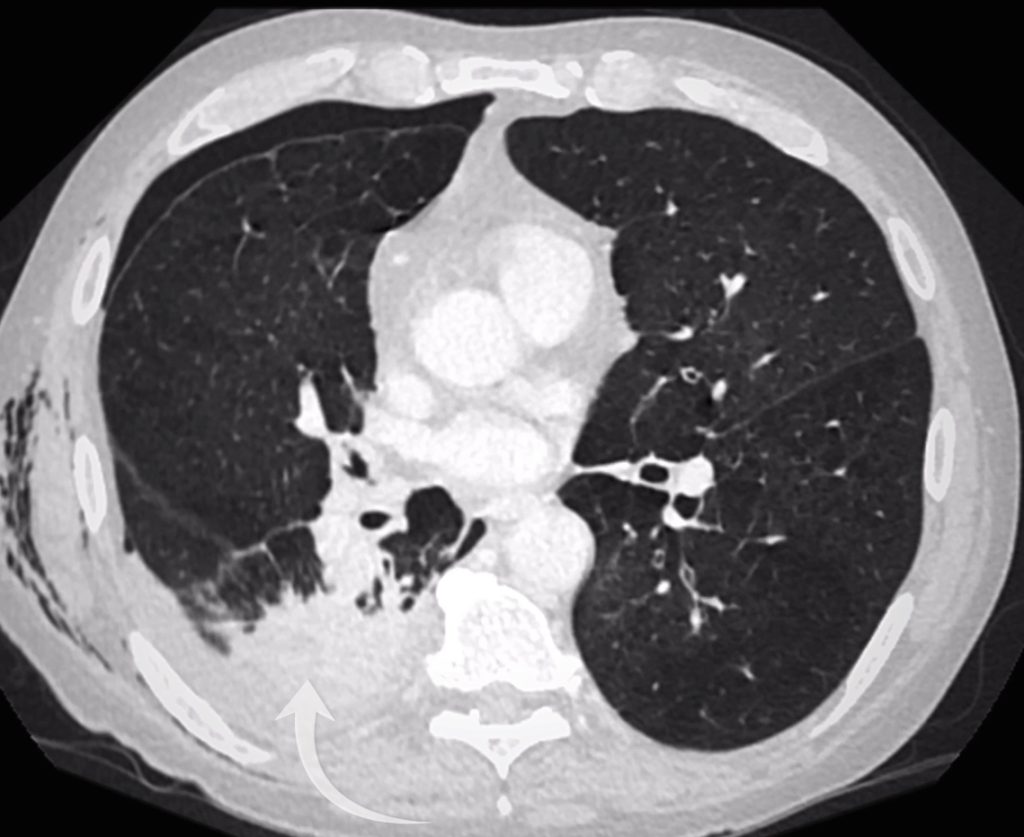

- The two lung opacities are confirmed:

- One in the apical right lower lobe (corresponding to the opacity behind the hilum).

- One in the right upper lobe.

The chest drain is out side of the pleura (bottom arrow) and the pneumothorax persists (top arrow). There is a small right pleural effusion.

CT confirms a right upper lobe opacity accounting for the right mid zone opacity on chest X-Ray.

A right lower lobe opacity accounts for the opacity seen overlying the right hilum on chest X-Ray.

Spiculation

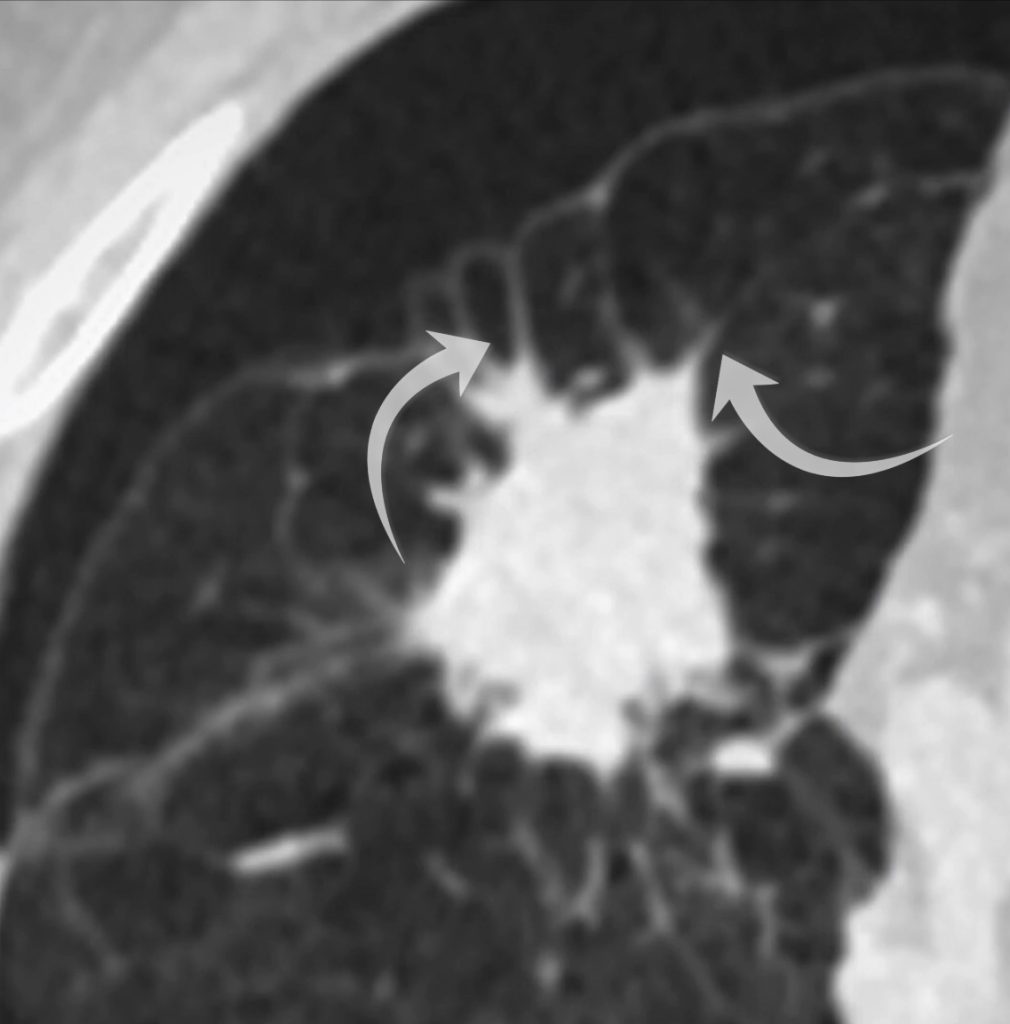

Examining the right upper lobe lesion in more detail, we see small spicules radiating from it. A spiculated lesion raises concern for a primary lung cancer. In my experience however you need to adopt a little caution when the underlying lung is abnormal as with severe emphysema a lot of lesions can look spiculated!

The right upper lobe lesion is spiculated.

PET-CT review

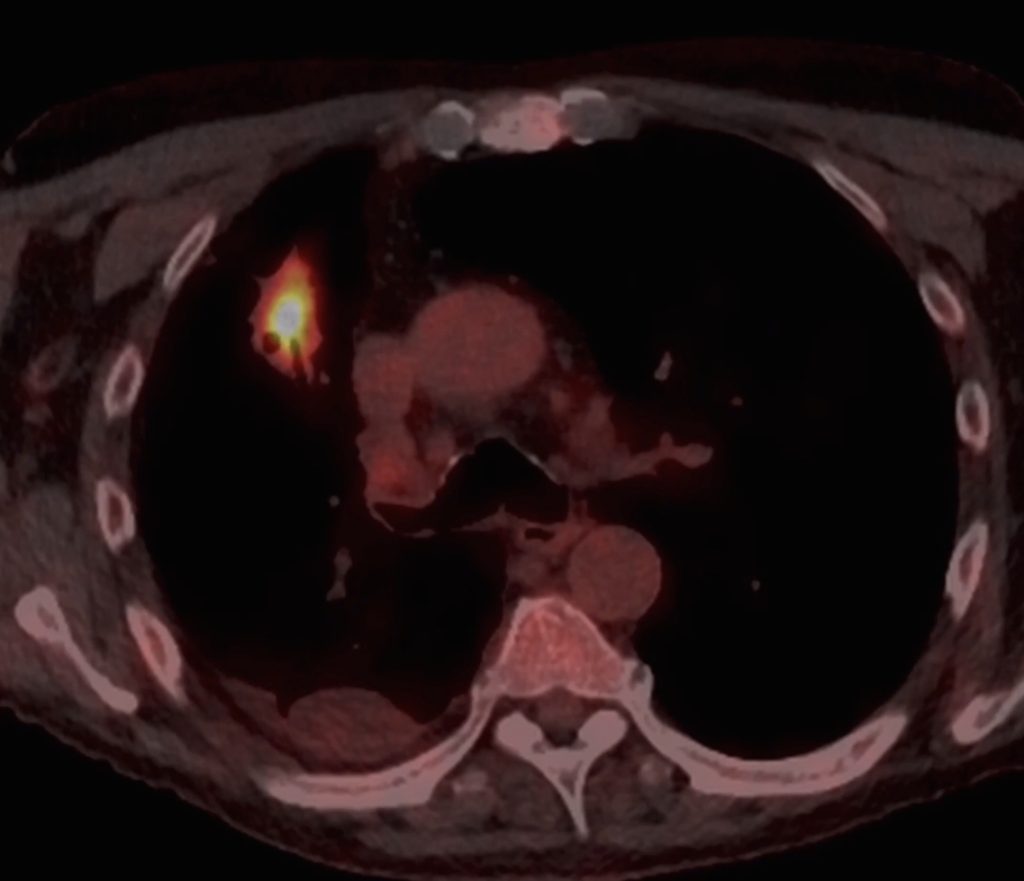

Since the patient’s inflammatory markers were elevated, but the appearance was concerning, a PET-CT scan was performed.

Both opacities were FDG-avid meaning malignancy couldn’t be ruled out.

On this image we can see FDG avidity within the right upper lobe lesion on PET-CT.

Follow up

What happened next?

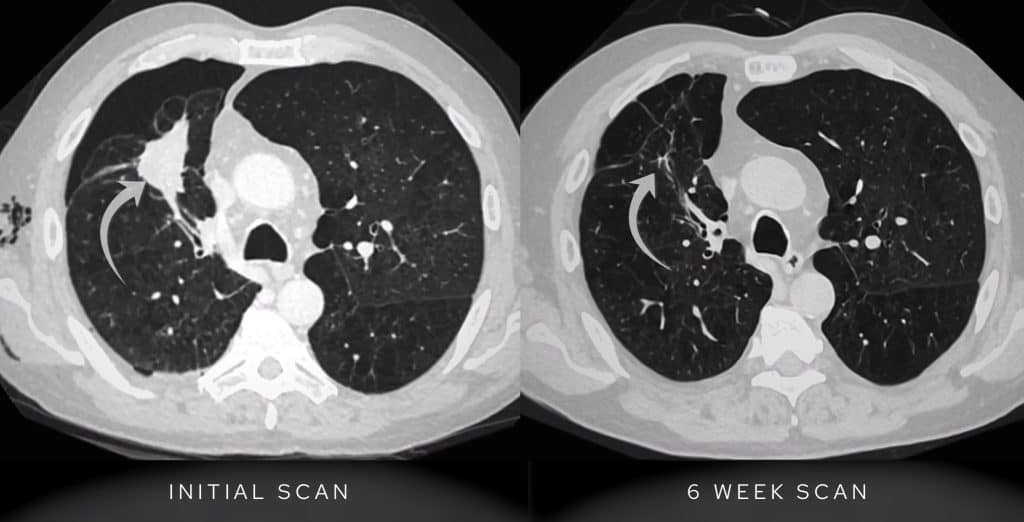

A repeat CT scan was performed 6 weeks later. Both opacities had almost completely resolved, meaning they were likely benign rather than malignant.

Repeat CT shows almost complete resolution of the right upper lobe lesion meaning this is not malignant.

KEY POINTS

Don’t miss a pneumothorax!

I don’t consider a chest X-Ray fully looked at until I have zoomed up on the apices and looked for both a pancoast tumour and small pneumothorax. If you have both a pleural line and lack of lung markings then bingo you have a pneumothorax.

Lung lesions on a background of emphysema almost always warrant workup to exclude lung cancer. If there are symptoms of a pneumonia then often follow up imaging can provide reassurance if the lesion resolves.