Solitary pulmonary nodule

On chest X-Ray and CT

Introduction

A solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN) is a common and often incidental finding on chest imaging, defined as a single opacity measuring less than 3 cm in diameter. The differential can range from benign granulomas to a malignant primary lung cancer. While most are benign, it is really important to know how to distinguish malignant nodules from these.

In this article we will go through a case of a solitary pulmonary nodule found on chest X-ray.

We will go through the workup of the case before discussing how to differentiate benign and malignant nodules whilst looking at nodule risk models and follow-up guidelines as well as lung adenocarcinoma spectrum lesions in a bit more detail.

Case introduction

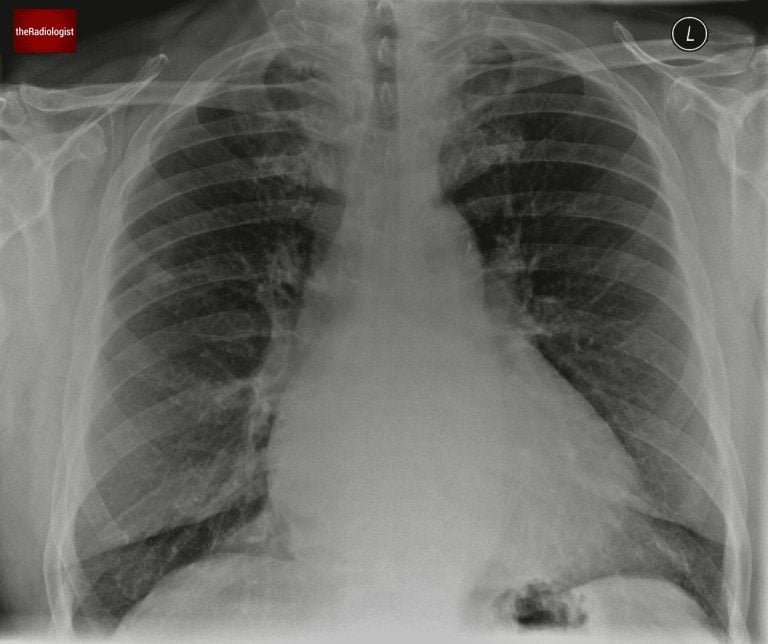

Let’s go through a case of a male in his 70s who presents with breathlessness. He has a PA chest X-Ray. Have a look at the X-Ray below. Is there anything abnormal that you think should be flagged?

PA view of a chest X-Ray of a male in his 70s

Video explanation

Here is a video explanation of this case: click full screen in the bottom right corner to make it big. If you prefer though I go through this in the text explanation below.

Case findings

Firstly let’s look at the heart.

- The heart appears enlarged, with a cardiothoracic ratio exceeding 50%. While this metric has limitations, it’s a quick way to identify potential cardiomegaly in the appropriate clinical context.

- There are signs of left atrial enlargement, evidenced by widening of the carinal angle.

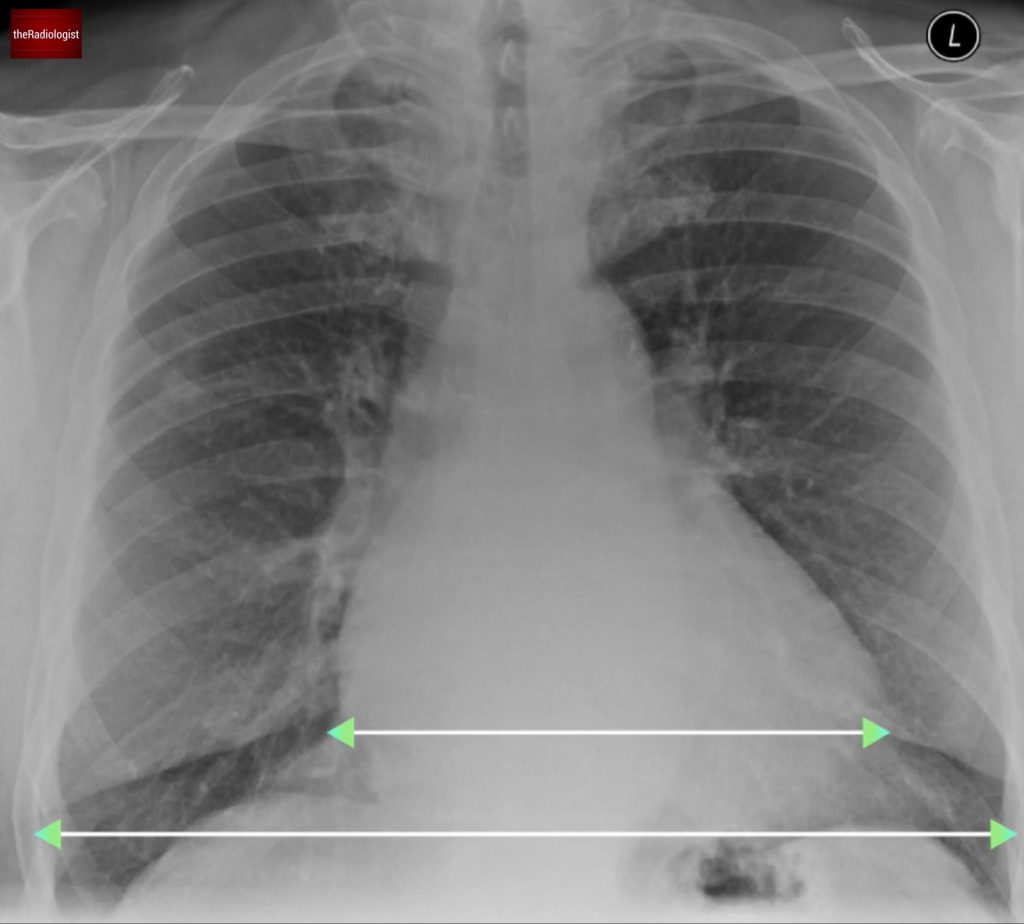

Measure the cardiothoracic ratio – the largest diameter of the heart divided by the largest internal diameter of the thorax (measure between the inner aspect of the ribs). This metric has limitations but anything significantly over 0.5 is suggestive of cardiomegaly.

Measure the carinal angle – anything over 90 degrees is suggestive of pathology. One of the most common causes of a widened carina is left atrial enlargement. If you see mediastinal node enlargement elsewhere, you may suspect subcarinal node enlargement.

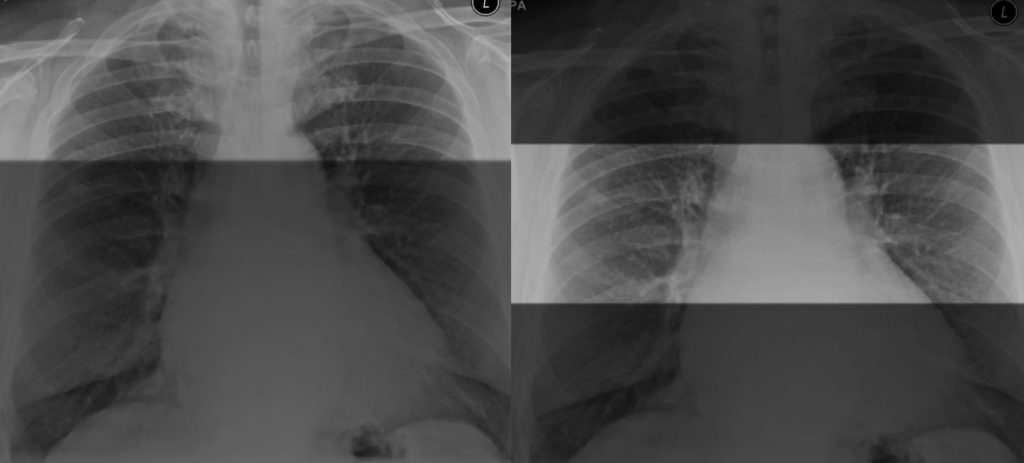

Secondly let’s look at the lungs. Finding lung nodules on chest X-Ray can be tricky. I find it useful to split the lungs into upper, mid and lower zones and compare side by side.

Splitting the lungs into upper, mid and lower zones and then comparing sides can help identify a lung nodule.

Inverting the film can also help bring out some nodules and give your eyes another chance to review the film from another perspective.

If we do so we will find a nodule here within the right upper zone.

Inverting the film can give your eyes another chance to catch something.

Differential diagnosis for solitary pulmonary nodule

Finding a solitary pulmonary nodule on chest X-Ray isn’t uncommon, after all excluding a worrisome lung nodule or mass is a common indication for performing a chest X-Ray.

For this reason it’s important to have a solid differential diagnosis for these cases. The differential is wide and we can go through this in the table below.

| Category | Cause | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Malignant | Primary lung cancer | Including adenocarcinoma (usually peripheral, can start life as a groundglass nodule becoming more solid over time), squamous cell carcinoma (classically cavitates), small cell lung cancer (not common to present a solitary pulmonary nodule as more a central lesion with mediastinal node enlargement). Carcinoid tumours can be seen as a well defined nodule. |

| Lung metastases | More likely to present with multiple nodules but can be seen on CXR initially as a single nodule. Typically from breast, colorectal, renal or head and neck cancer but the potential list of primary cancers leading to lung metastases is long. In younger patients consider osteosarcoma (can calcify), germ cell tumours and melanoma. | |

| Infective | Bacterial | TB (discrete small nodules with a predilection for the upper lobes, particularly the right), non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), nocardiosis, actinomycosis. |

| Fungal | Histoplasmosis (calcify over time), coccidiomycosis, blastomyccosis, cryptococcosis, aspergilloma (fungal ball within a pre-existing cavity) | |

| Parasitic | Hydatid disease (echinococcus) | |

| Benign tumour | Hamartoma | Well defined nodule which can calcify and on CT classically show some fat density. Fat density within a nodule usually means this is benign with some rare exceptions. |

| Lipoma | Uncommon. Fat attenuation on CT. | |

| Inflammatory | Sarcoidosis | Usually multiple ‘bronchocentric’ nodules but possibly could be seen as a single nodule on CXR |

| Granulomatous with polyangiitis (GPA) | Usually multiple, can cavitate. | |

| Rheumatoid nodule | Usually peripheral and well defined. Can cavitate. Can be multiple. | |

| Vascular | Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (AVM) | Well defined, look for a feeding artery/draining vein. |

| Pulmonary infarct | Usually peripheral and wedge shaped. Suggests an underlying PE or septic embolism. | |

| Congenital | Bronchogenic cyst | Well defined, usually related to the mediastinum so not a common cause of a lung nodule. |

| Sequestration | Again uncommon but can appear mass like. |

Case workup

Unless the nodule has been seen previously and is a known entity, once you have found a solitary pulmonary nodule, this will usually need a CT scan to further characterise the nodule and look for any other findings that may give us a clue as to what the aetiology is. Let’s have a look at the CT scan in this case.

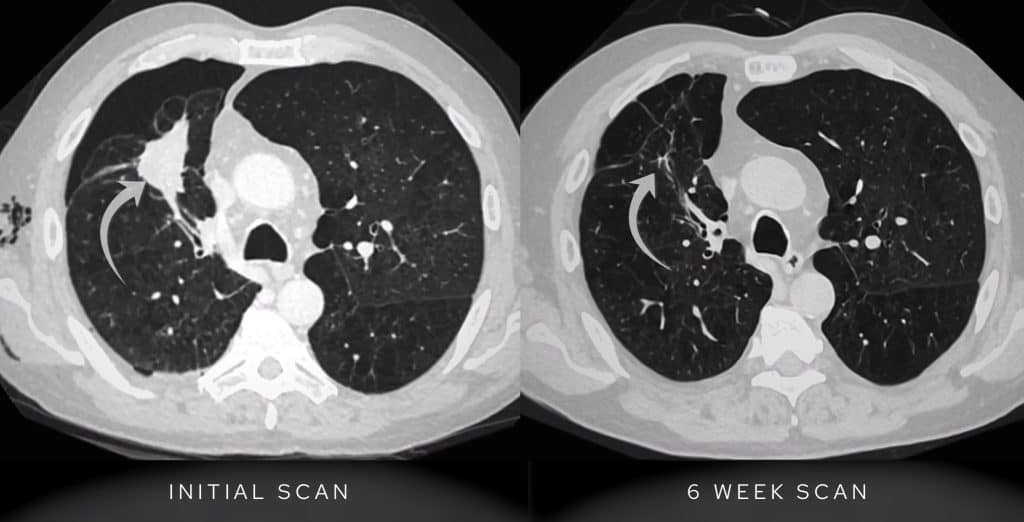

The CT confirms the presence of a subsolid nodule in the right upper lobe.

- This nodule exhibits both ground-glass and solid components: once you see this particularly in someone with a smoking history, you need to consider a primary lung adenocarcinoma.

- Comparing with prior imaging we can see the lesion was present previously. The nodule has evolved, becoming denser and developing a larger solid component over several years: this is a key feature of lung adenocarcinomas. We will come onto this in more detail a little lower down.

CT confirms a lesion within the right upper lobe which has become more solid when compared with the previous CT scan of 2 years prior.

On PET-CT the nodule demonstrated FDG avidity, raising suspicion for malignancy, although note that when lung adenocarcinoma spectrum lesions are in their early phase PET-CT findings can be unreliable. On PET-CT there was no evidence of nodal or distant metastasic disease.

PET-CT shows the lesion within the right upper lobe shows FDG avidity.

CT-guided biopsy confirmed a lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma as suspected on the CT imaging.

CT guided biopsy of the lesion confirmed a primary lung adenocarcinoma.

1The lesion was resected surgically, preventing progression to invasive disease or metastasis with a good outcome for the patient. This is a really important case highlighting the importance of reviewing chest X-Rays carefully for solitary pulmonary nodules.

KEY POINTS

Picking up a nodule on chest X-Ray can be tricky especially when they are subtle.

Use tricks like splitting the lungs into zones and inverting the film to increase your yield when it comes to picking up solitary pulmonary nodules.

Compare to any previous films and remember a slowly growing nodule in a smoker could represent a lung adenocarcinoma.

Differentiating benign and malignant nodules

How do we differentiate between benign and malignant lung nodules on chest X-Ray and CT? There are no hard and fast rules but there are some factors we can look at to try and work out the probability that a nodule is benign or malignant.

- Size: smaller lung nodules less than 2 cm are more likely benign although early lung cancers and metastases start life as a small nodule. Remember that if a lesion is over 3 cm it is technically termed a ‘mass’ rather than a ‘nodule’.

- Border: a smooth border makes a benign nodule more likely (although not certain). Remember metastases and carcinoid tumours can have smooth borders. A ‘spiculated’ appearance with linear spicules arising from the lesion points more towards a primary lung cancer.

- Pattern of calcification: central calcification or ‘popcorn calcification’ suggests a benign cause whilst tiny foci of punctate calcification make a malignant nodule still possible.

- Presence of fat: almost certainly means a benign nodule, most commonly a hamartoma (both fat and calcification make this almost certain). There are rare causes of a malignant fat containing nodule such as renal cell metastases and liposarcoma.

- Growth pattern: in most circumstances, stability of a completely solid lung nodule for 2 years means it is very likely to be benign and most follow up pathways will mean no further follow up is necessary. Note this does not apply for subsolid nodules (ie with a groundglass component). A volume doubling time of more than 450 days is suggestive of a benign nodule.

- Groundglass and solid components: having both solid and groundglass components, particularly also with dilatation of airways within and a smoking background is suggestive of a lung adenocarcinoma (see section below).

- Intrapulmonary lymph nodes/perifissural nodules (PFN): these are benign nodules that do not need follow up but how do we recognise these? I use the factors below. Times where you can be caught out will usually be if there is a known history of malignancy or nodules within the upper lobes so these are ones to be more cautious with.

- Straight edges: these nodules are classically triangular and have straight edges. You may need to review on sagittal or coronal views to characterise fully

- Perifissural position. May be peripheral with a ‘pleural tag’ a faint line communicating with the pleura

- Usually less than 1 cm in size

- Usually not within the upper lobes.

Nodule risk models

Rather than use subjective intuition, we can use scoring systems which use objective factors to estimate the probability of cancer. Let’s look at the Brock model and Herder model.

Brock model

The Brock score was developed from data in the Pan-Canadian Early Detection of Lung Cancer Study and is designed for incidental lung nodules and works out the probability that a lung nodule will be diagnosed as cancer within a 2-4 year follow up period. It is used within the British Thoracic Society guidelines for nodule work up (2015).

It uses factors such as age, family history of lung cancer, sex, presence of emphysema, nodule size, nodule spiculation, nodule site (upper lobes have increased risk) and nodule count (single nodules more likely lung cancer) to work out a probability of lung cancer.

Herder model

The Herder model incorporates PET-CT findings which makes it a useful tool when planning biopsy or surgery. A higher FDG uptake on PET-CT significantly raises the likelihood of malignancy (although note there are caveats to this with carcinoid tumours and early stage lung adenocarcinoma showing lower uptake).

The British Thoracic Society suggests using the following scale to help feed into the model:

- No uptake: uptake less than background lung

- Faint uptake: uptake less than or equal to mediastinal blood pool

- Moderate uptake: uptake greater than mediastinal blood pool

- Intense uptake: uptake markedly greater than mediastinal blood pool

Nodule follow-up guidelines

There are different nodule guidelines in use, namely the American guidelines – the Fleichner Society guidelines and the UK version from the British Thoracic Society. As I work in the UK I am going to dive deeper into the British Thoracic Society guidelines.

British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines 2015

These guidelines apply to patients aged 18 and over. If there is more than one nodule, apply this to the largest nodule. Essentially solid nodules stable on volume measurement at 1 year (ie less than 25% growth) or stable on diameter measurement at 2 years don’t need further follow up. With BTS you’re measuring the maximal diameter rather than average of short and long axis as is the case with Fleischner.

At the heart of the BTS guidelines are the Brock and Herder models talked about above.

Don’t follow up:

- Nodules less than 5 mm

- Benign pattern calcification

- Perifissural nodules – look for straight edges all the way round, see above.

Solid nodules

Solid nodules of 5 mm or more are followed up:

- CT at 1 year for 5 mm nodules. If the volume is stable (ie volume doubling time calculated at more than 600 days) then discharge. For further work up if less than 600 days and definitely so if less than 400 days.

- CT at 3 months for 6 mm and 7 mm nodules then again at 1 year if stable.

- If 8 mm or more calculate a Brock score – if less than 10% risk do a scan at 1 year as above. If over 10% risk then consider a PET-CT and calculate a Herder score.

- High risk over 70% on a Herder score needs further work up. Less than 10% and go for CT surveillance. Anything in between and it’s your call taking into account the patient’s wishes and fitness as well as what can reasonably be biopsied.

Subsolid nodules

For ‘subsolid’ nodules the rules are slightly different. Subsolid nodules refer to any nodule that is not completely solid and can be seen as either:

- Pure groundglass nodules

- Part solid nodules (with both groundglass and solid elements)

With these the concern is a of a lung adenocarcinoma spectrum lesion – these can grow slowly and start life as a pure groundglass nodule, becoming more dense and larger over the course of many years.

For this reason subsolid nodule guidelines usually need to extend out longer and in the case of the BTS guidelines, go out to 4 years rather than 2 for solid nodules.

For subsolid nodules of 5 mm or more, start with a 3 month scan – if the nodule goes away great. If it hasn’t improved then 4 year stability post baseline will be needed with scans at 1, 2 and 4 years.

If at 3 months the Brock score is over 10% then you may consider doing a biopsy or resecting the lesion depending on the patient’s wishes and fitness.

Lung adenocarcinoma spectrum lesions

Let’s look at lung adenocarcinomas in more detail. Lung adenocarcinoma is the most common subtype of lung cancer, accounting for approximately 40% of non-small cell lung cancer cases. Its classification hinges on the concept of lepidic growth, where tumor cells spread along alveolar walls without significant invasion.

Essentially we can categorise into pre-invasive lesions which show on CT as pure groundglass lesions, minimally invasive lesions which start to show a solid component and then invasive lesions where solid components show as a more significant part.

Let’s look at some of the forms of adenocarcinoma in a bit more detail. In general the more solid component seen the more pathologically invasive the lesion is.

1. Pre-invasive Lesions

These lesions exhibit no stromal, vascular, or pleural invasion and are usually seen as a pure groundglass nodule.

Atypical Adenomatous Hyperplasia (AAH)

- Small lesions (<5 mm).

- Purely ground-glass nodules on CT.

- Considered a precursor to adenocarcinoma.

Adenocarcinoma in Situ (AIS)

- Overall size ≤3 cm.

- Entirely lepidic growth pattern (tumor cells growing along intact alveolar walls).

- No stromal invasion.

- CT Appearance: Pure ground-glass nodule or minimally solid nodule.

- Excellent prognosis after complete resection.

2. Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma

- Tumor ≤3 cm now with a small invasive component: ≤5 mm stromal invasion.

- CT Appearance: Ground-glass nodule with a small solid component which usually represents the focus of invasion.

- High survival rates with appropriate treatment.

3. Invasive Adenocarcinoma

These tumors have significant stromal, vascular, or pleural invasion measuring more than 5 mm in size. There is a wide and complex classification of different histological subtypes including lepidic predominant, acinar, papillary and solid. These lesions are more often mucinous as opposed to non-invasive adenocarcinomas which are more often non-mucinous.

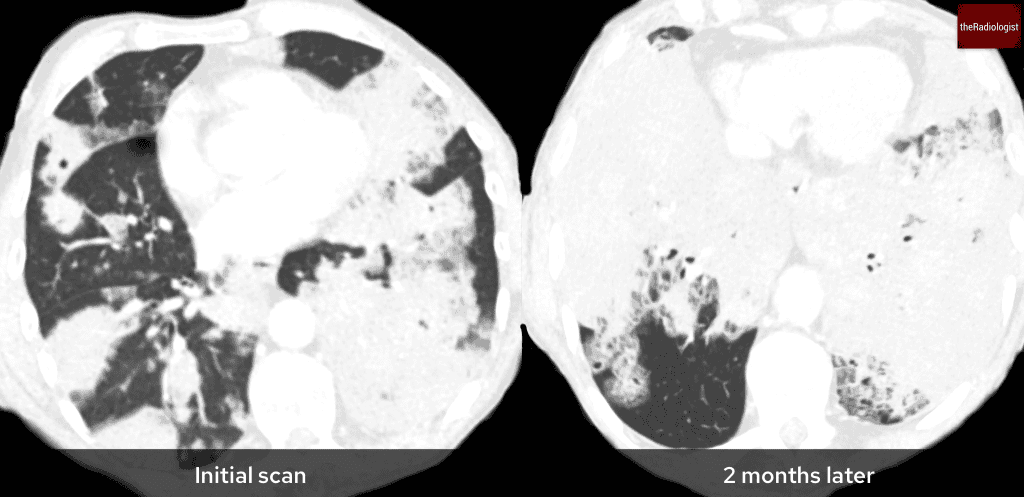

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma can present as multifocal consolidation that does not respond to antibiotic therapy and progresses on serial CT scans. This will usually need to diagnosed on lung biopsy and unfortunately carries a poor prognosis.

Here is a separate case of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma presenting initially as multifocal consolidation with no response to antibiotics and worsening 2 months later. The diagnosis was confirmed on CT guided lung biopsy.